OXFORD'S EXOTIC ANIMALS

Credit: Oxford University Press

OXFORD'S EXOTIC ANIMALS

Some animal anecdotes relating to Oxford from ‘Menagerie’ by Caroline Grigson

Published: 8 May 2018

Author: Caroline Grigson

Share this article

Some of the earliest records of exotic animals in England relate to Magdalen College in Oxford, including the blood-thirsty practice of bear-baiting, that is staging fights between tethered bears and bulldogs. In the Michaelmas term of 1486 a special fight was staged in the College, so pleased were the Fellows, that they invited the bear’s owners to dine and rewarded its keeper with four pence. In contrast, it is said that amongst the gardens, orchards, dovecots and fish ponds of the College was a small collection of animals, including peacocks, swans and hares; a few years later the fellows presented some small monkeys to Henry VII, who reciprocated by donating a she-bear to the College.

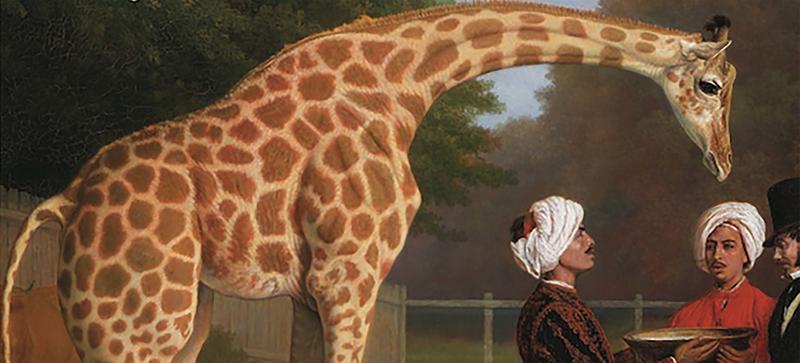

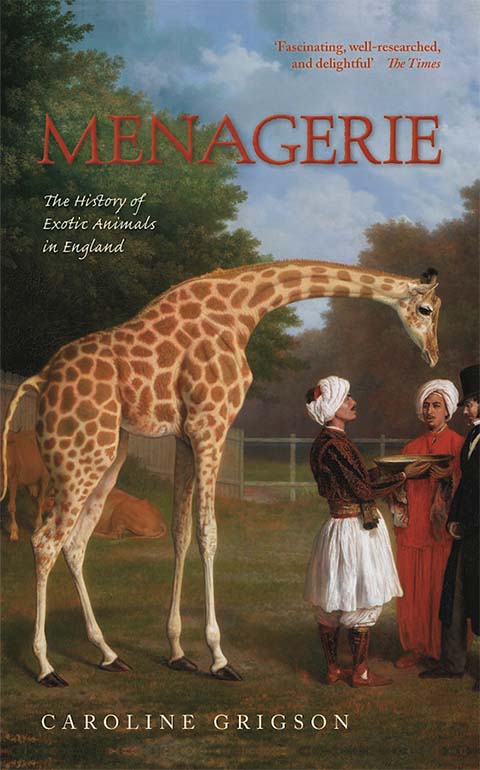

Cover of Menagerie, The history of exotic animals in England

Credit: Oxford University Press

In 1635, despite being “prohibited by the Vice-Chancellors of Oxford and Cambridge” Thomas Ward managed to acquire a real live lion and to show it for money at Oxford Fair and at Sturbridge fair near Cambridge. This caused quite a sensation as most country people had never seen such a fierce exotic creature unless they had visited the Tower of London where lions and leopards had been incarcerated in the royal menagerie since the 12th century.

An Indian elephant calf, only five feet high, was brought to London from Java in 1675, it was put up for auction and ‘sold by the candle’ for the immense sum of £2,000. Its new owner made the most of his new investment by exhibiting the little elephant in pubs in London and then touring it around the south of England as far as Oxford.

A lion from A General History of Quadrupeds by Thomas Bewick

Ten year later an even more exotic curiosity, a rhinoceros, arrived from the Far East; it did not live long - the story goes that “after some stay in London [the rhino] was carried to the University of Oxford, where by the over Curiousness of some Gentlemen in trying the utmost strength of that Creature loaded it with so many sacks of Corn till it sunk under the Burthen and broke its Back”.

A rhino from A General History of Quadrupeds by Thomas Bewick

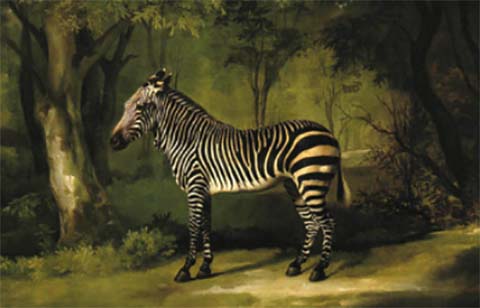

With the advent of the eighteenth century exotic animals arrived in Britain in ever increasing numbers, many of them were toured around the country in travelling menageries to be displayed to the public. When in Oxford they were shown at Goose Green, or in pubs such as the Chequers Inn in the High Street. For example, the Oxford Journal reported in 1757 that “The amazing dromedary from Persia and lofty camel from Grand Cairo [to be seen] at the Chequer Inn in this city”. When John Pinchbeck’s travelling menagerie, which included “an oriental tiger, a magnanimous lion, a ‘real’ Bengal tiger, a beautiful leopard, a voracious panther, and a ‘man-tyger’, arrived in Oxford in 1771, the star turn was the “Queen’s Ass,” that is, a zebra, much like an ass, but decorated with black stripes. Queen Charlotte had received the zebra as a gift and it had been viewed by several thousand people when grazing in a paddock near her house in London. She was deeply unpopular so it was not long before bawdy verses and scurrilous cartoons of the “Queen’s Ass” began to appear. Eventually she gave the zebra to its keeper who sold it to Pinchbeck.

Zebra reproduced from the painting owned by Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

After Oxford the menagerie travelled north towards Newark where the much-maligned zebra expired. Not one to disadvantaged by such a sad event, Pinchbeck had her skin stuffed and carried on displaying her in his menagerie. The Queen’s Ass ended her days in the Leverian Museum in London. “When Mr Pidcock was exhibiting his grand cassowary [a large flightless bird from Java] at Oxford [in 1779] it layed an egg, and on the Proprietor's advertising that such a circumstance had happened, a number of Collegians, who doubted the truth of this assertion, went in a body to see it; they had prepared themselves with a small drill, with which they made two holes, one at each end of the shell; this done, a person in company was desired to blow through the shell, and it produced a fine yolk: the Collegians, having ocular demonstration, went away satisfied. This caused a great number of the inhabitants of Oxford, to come and see the bird and the egg mentioned.”

When excavating ice-age deposits in Kirkdale Cave in Yorkshire, William Buckland (Oxford’s first Reader in Geology) found a portion of a skull which he thought might be that of a young hyaena, but not having a suitable skull to compare it with he ordered a young hyaena to be brought from South Africa to be slaughtered for the sake of its skull. A little hyaena, named Billy, arrived in 1821, but he was so playful and good tempered that his life was spared and he became a much-loved family pet; nevertheless, he made an unusual contribution to science. Buckland had excavated coprolites (animal droppings) in Kirkdale Cave, but he was uncertain what species had produced them; after dining on bones Billy’s droppings were found to be identical to those found in the cave proving it to have been a hyaena den.

Menagerie author Caroline Grigson is a zoologist and former curator of the Museums of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, and today an honorary professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology. The subjects of her numerous publications range from prehistoric animal exploitation to the history of natural history and its relationship to art in eighteenth-century London. The book is published by OUP on May 10th, 2018, for £12.99.