OXFORD HISTORIAN SHORTLISTED FOR THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE

OXFORD HISTORIAN SHORTLISTED FOR THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE

John Blair has transformed our view of the Anglo-Saxons

Published: 3 June 2019

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

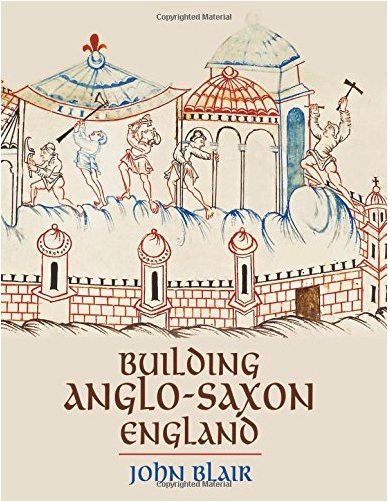

As his Oxford colleague William Whyte puts it, the Dark Ages are now less dark because of Building Anglo-Saxon England, the monumental opus of John Blair, Professor of Medieval History and Archaeology at Oxford and a fellow at The Queen’s College. The book has been been shortlisted for the prestigious Wolfson History Prize, to be announced in London on June 11.

Professor John Blair

Credit: Professor John Blair

Not only are the Dark Ages more illumined, but more colourful too thanks to the magnificent effort of Princeton University Press from its Oxford base in Woodstock, which has somehow managed to produce almost 500 pages of colour-illustrated, semi-large format brilliance for a more than fair price.

The book concerns the period 600-1000, focussing on buildings rather than more familiar jewellery hoards.

If you studied this period as part of the Honour Moderations course upon arrival at Oxford, you will remember, fragmentarily and perhaps through a mist of library stress, textual analysis of the Venerable Bede of the most technical variety, haggled over fiercely by the community of scholars who counted it their turf.

Since circa 1990, the whole subject has been gloriously upended by non-textual archaeology including, painfully for the textual scholars, amateur contributions by metal detectorists celebrated fictionally by the TV hit The Detectorists.

As Blair puts it, ‘archaeology is all we have.’

But what we have isn’t half bad.

A vast range of digs over the past thirty years have completely transformed our notion of Anglo-Saxon Britain, away from the documented regions (Wessex and Mercia), and towards the undocumented but now visible – thanks to archaeology – areas, particularly around the Wash.

‘There was a western arc of culture, Wales down to Cornwall and coming in towards the west Midlands along the River Severn. But the central discovery assembled in the book concerns the powerful and quite distinct culture that coalesced around the Trent and the Ouse, the rivers that empty into the Humber Estuary.’

Blair admits that one impetus behind his inquiry over the past five years has been an ‘irritation’ at public debates about recovering a native English identity against the backdrop of impending BREXIT. ‘What is English identity? People have difficulty grasping it because it doesn’t really exist.’

Regional difference runs through the book like the writing in a stick of Blackpool rock. Blair writes, ‘Far more than is usually acknowledged, the west – including for instance Gloucestershire and Shropshire – belonged to the Atlantic world of western Britain and Ireland, whereas the east – including for instance Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire – belonged to the North Sea and Baltic world of Scandinavia and the Low Countries.’ He continues, ‘National identities are constructs; a much broader and deeper continuum of European regional identities underlies them.’

Citing George Molyneaux’s 2015 book The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century, Blair agrees with Molyneaux’s assessment that claims for English exceptionalism are basically meritless, and that England was in fact part of a heterogenous ‘outer Europe’. What Blair emphasises is the pervasive Scandinavian influence on Eastern England.

Ultimately, he notes very early on, it was the misfortune of the period in question that the Anglo-Saxons built in ‘transient timber’ rather than earth works and stones like the Iron Age and Romans, and again by the Normans following the Conquest. For no other reason did the period 600-1000 become obscure in collective memory.

The only 'Anglo-Saxon' timber walls still standing. Although Greensted church (essex) was built shortly after the Conquest, it is a witness to one variant within a broad tradition that reflects Scandinavian influences.

Credit: Page 61 of Building Anglo-Saxon England by John Blair (Princeton University Press, 2018).

There does remain a timber church in the Essex village of Greensted, which although built shortly after the Norman Conquest still connects back to an inherited tradition. Comparable structures are to be found in places like Latvia.

John says that when an undergraduate in Oxford in the 1970s, his mainstay was already the Oxford Archaeology Society. He was preoccupied with the period ‘long before I was even an undergraduate.’

His only regret is that Oxford has never quite managed to host a joint-honours degree combining history and archaeology, the two schools sitting in different Divisions of the University and thus awkwardly far away from each other in institutional arrangement. He thinks this may still change, adding that in practice the conversation and communications across the different communities of scholars have become much, much better than they were once.

Building Anglo-Saxon England by John Blair (Princeton University Press, 2018).