OXFORD'S FRAUDSTER

OXFORD'S FRAUDSTER

The cautionary tale of Robert Peters

Published: 10 June 2019

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Adam Sisman, the biographer of Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper (Christ Church, 1932) and spy novelist John le Carré, has painstakingly rivetted together the life of a serial fraudster obsessed with Oxford.

Robert Peters (1918-2005) wasn’t a venal sort of fraud, although he was convicted at different times of stealing and amassed a superb library by buying books on credit and never settling his account – a genteel form of stealing, one might argue, but still stealing.

No, his real preoccupation was status, and he sought it in two places: the church and academia.

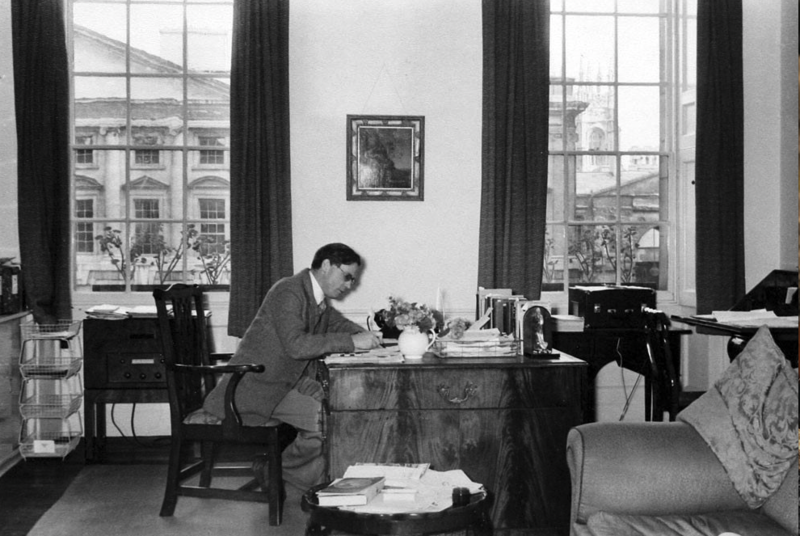

Hugh Trevor Roper in his rooms at Christ Church

Enter mid-Twentieth Century Oxford, which had plenty of both, and Hugh Trevor-Roper, who in 1958, where the tale properly begins, was at the height of his 44-year-old powers as Regius Professor of History in Oxford Sisman notes that Trevor-Roper had made big money from his 1947 best-seller The Last Days of Hitler, upon which he had purchased a grey Bentley that he parked ostentatiously in the middle of Tom Quad, Christ Church.

It’s a luminous detail concerning Trevor-Roper’s own boisterous sense of self, an irreverent contrarian as well as a church-baiter.

Naturally then – we’re back to 1958 – he was intrigued to get a letter out of the blue from a Miss Gibson, North Oxford resident, on behalf of her lodgers, a couple, who were being persecuted improperly by the Bishop of Oxford.

To Trevor-Roper, this was cat-nip.

Peters duly turned up and was seated in Trever-Roper’s History Faculty office.

Peters was a ‘…small, chubby-cheeked, bespectacled man with thinning hair and an earnest manner, who spoke with a slight lisp.’ He explained at length how his role as an officiating priest in Oxford had become tangled up with his candidacy for a B.Litt as a student of Magdalen College, and why he was now being threatened by the Bishop of Oxford.

Trevor-Roper, notes Sisman, never questioned the man’s veracity and sought to help by having quiet words with the right people.

Subsequently, when Trevor-Roper became wise to Peters, he opened a file on the man and populated it for the next twenty years.

‘Our old friend’ would crop up again here, there and indeed everywhere in an astonishing example of globetrotting agency, long before international travel became affordable or ‘normal’ in the Easyjet sense.

When confronted about degrees he claimed to possess but didn’t, or references, which he readily forged, he’d explode in a vile rage before eventually disappearing overnight, sometimes abandoning a wife, going to ground, going abroad for a ‘holiday.’

Despite wide exposure in the press, nothing at all deterred Peters from further frauds. He seemed impervious to criticism and without conscience.

Despite being widely exposed, Peters just kept going in his deceits and kept on being successful at them too

Credit: Daily Mirror

Just days or weeks after being exposed, he’d reinvent himself with charming confidence and complete self-belief, mounting a brazen campaign of applying for new academic or seminary posts in universities all over the world, invariably targeting the misty faultline between church and university, his minor clerical status covering for his lack of theological credentials.

Typically, he’d claim a first-class degree from Oxford: enough in the 1950s to obtain an academic post in America or the former British Empire. The reality was that he’d been expelled from Magdalen early in 1959 and was academically no better than ‘a human parrot,’ as someone put it, plagiarising whatever he wanted, wherever he could obtain it.

The truth caught up with Peters all the time. He was arrested at gun point in Switzerland for not paying a hotel bill, as Sisman notes sagely, in Switzerland almost ‘a capital offence’.

Later, he was deported from America three times; and from Canada twice. He was ejected from an apartheid-era, white South African college for stirring up racist aggression – quite an achievement notes Sisman.

Along the way he wooed women rapidly, marrying eight or nine times, dropping them like crisp packets when his next deception caught up with him, or occasionally being jilted by the wise ones.

He was predatory and inappropriate towards women who were always much his junior, and habitually lied about his age.

He gulled softer mentor targets in the church who fell for his pleas of help and charity, even to the point of agreeing that he must reform, telling journalists on certain occasions that he had repented and would henceforth be honourable – a classic instance of distraction and further deception.

Deprived of Oxford he came back later and tried to re-negotiate his standing at Magdalen, which was refused.

The moral of the story is not just how little the innumerable setbacks bothered him, being a narcissistic personality type, but more worryingly how little they impeded him from mounting the next fraud. There was no ultimate reckoning. He just kept going, brass-necked unto the grave.

Cut out of the Oxford heaven, he resorted to founding a string of colleges in which his board of trustees was essentially himself and his dogsbody wife, his roster of students never more than half a dozen, and everything arranged around his own, ugly sense of superiority.

Around the time that polytechnics became universities in the UK, he briefly gulled one ‘Quality Assurance Team’ into approving his degrees. Well into his seventies he was still going strong, long after most of the wise birds who knew his tricks had pre-deceased him.

In short – and this is the main run of the book’s narrative – Peters was an inveterate con and fantasist. He wanted standing more than money and managed to combine the deadly combination of ordination (which was true although he was later defrocked) and academic ambition (which was thoroughly misplaced) to assert and re-assert himself hundreds of times into religious and academic roles for which he possessed no qualification. When he died in 2005 he died in total obscurity, in Kettering. His death certificate was untrue in almost every detail, suggesting that his wife had been conned as well.

A gift to any biographer, the Robert Peters file had long been known to Sisman, who published a superbly detailed biography of Trevor-Roper in 2010.

Sisman recalls, ‘Like most people I had not heard of Peters before. I first noticed his name on the cover of a thick folder, inscribed by fountain pen in Trevor-Roper’s lucid, distinctive hand.’

‘Studying Peters,’ writes Sisman, ‘is like tracking a particle in a cloud chamber: usually one cannot see the man himself, but only the path he left behind.’ Full praise to Sisman for the intricate detective work he has carried out here, without overburdening a juicy tale that has greatly amused everyone who’s read it.

But it’s a funny one in the other sense too.

Sisman insists that his purpose is ‘to entertain, not to instruct,’ while acknowledging that ‘Some readers, alarmed by Peters’s success as a con man, may feel that this story is a cautionary tale.’

The book jacket has Simon Winchester saying that the story is ‘utterly mad, and wholly delightful’.

Researched and written just before the tide of populist politics engulfed western Christendom, and as the global church, both Catholic and Protestant, slid ever deeper into paedophilia crises, the book is certainly amusing, but it cannot be ‘wholly delightful.’

In one instance Peters, who traded under a litany of different names, found himself on a Church memorandum warning of two ‘wandering priests’ – the other one Roger Greaves, self-styled ‘Bishop of Medway’, ‘who had been convicted of serious sexual offences against adolescent boys and, like Peters, claimed Old Catholic orders.’

Whichever way you spin it, this is not amusing at all.

Peters wasn’t a paedophile; merely an unpleasant, predatory misogynist.

But the church is the same institution throughout, incapable of manning its borders or controlling its members, rightful or bogus.

The universities in the narrative were better informed and somewhat less naïve, yet the reality is that Trevor-Roper was not only taken in by Peters but developed a sort of admiration for him, claiming at one point in a letter that he far preferred Peters to a naïve theologian who (disastrously) supported him.

This came years before Trevor-Roper was himself the victim on a much larger scale of fraud, when he foolishly authenticated Hitler’s diaries for the Times before they were shown to be forgeries, a career-destroying move especially for a man so used to destroying others.

And this is all pertinent, we discover, because shortly after the Hitler diaries catastrophe, the file on Peters abruptly stops. It was as if deceit suddenly became unfunny to the Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge, as he was by then, as it surely was for all the people touched by toxic Peters.