BOOKS FOR NOVEMBER

BOOKS FOR NOVEMBER

Whether locked down or not, the written word may well be your friend in November

Published: 5 November 2020

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

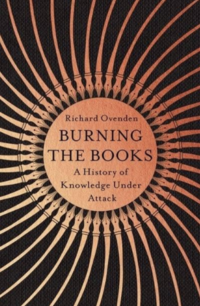

Bodley Librarian Richard Ovenden has published a timely book, Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack. He says the book arose from the revelation in 2018 that Home Office officials in London had destroyed an archive of disembarkation cards concerning the Windrush Generation of immigrants to the UK, thereby denying clarity in the event of disputed residency. Whether inadvertent mistake or something more sinister, the issue puts a sharp relief on the importance of archives, records, knowledge, public access to knowledge, transparency, accountability and that endangered thing known as truth.

The book traverses 3,000 years and it anything but dull. Byron’s friends destroyed his memoirs to save his reputation. Kafka’s executor Max Brod refused to do the same despite Kafka’s wish that he should. How does knowledge get preserved or destroyed?

Where state actors are concerned it becomes a very serious business. In 2018, notes the author, 4,400 metres of records appear to have been destroyed by the Government Records Service of Hong Kong. Earlier on, Ovenden cites George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four: ‘the past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth.’ You don’t need a history degree to see what’s going on here.

The later chapter on digital ‘inundation’ is timely, lucid and a must-read. The example drawn on is Flickr. Subscribers with lots of photos hosted by the for-profit company were suddenly told they would be restricted to just 1,000. The rest were erased at the flick of a switch.

The author details fascinating but strikingly under-resourced efforts to ‘preserve’ the web, ‘archive’ Twitter and ‘capture’ digital ‘knowledge’ before it falters and disappears into the obscure and friable land of servers.

The author makes a compelling case for re-realising the value of libraries and archives at the very moment when the tendency has been the opposite, to relegate them on the mistaken assumption that Google et al will do the job for free and with a similar public service ethos.

That is a desperately naïve assumption, says the author. What we now have instead is a murky world of privately-owned knowledge. ‘All of this data and technology has been created ‘for the purposes of modification, prediction, monetization, and control.’’ The term for this is ‘surveillance capitalism.’ We have outsourced the world’s memory to tech companies while forgetting that they are not disinterested actors.

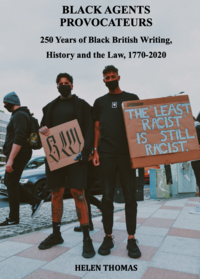

Oxford alumna Dr Helen Thomas (Exeter, 1989) has published a book available for free, to coincide with Black History Month. Black Agents Provocateurs, 250 Years of Black British Writing, History and the Law, 1770-2020 is a landmark book covering an enormous sweep of history. The culmination of twenty years of research, it tackles head on the intersection between law and literature, identifying a terrific range of individuals who in their different ways felt marginalised because of their race and decided to challenge it. Or, as Thomas puts it, ‘their writing reflected histories of alienated subjectivity fluctuating between rebellion and deference, liminality and public denunciations of racism.’ In the background is a broader emphasis on the underlying structures of language. This makes perfect sense but will be unfamiliar to many readers. We tend to hold legal structures to one periphery of our imagination, and creative literature to another, but both can be understood as ‘formalised attempts to structure reality through language.’ This matters greatly if you are a slave or an ‘emancipated’ one, whatever that might have meant in reality. Words became agency through protest, or through other forms of writing: plays, poems, novels, intellectual analysis as per this book, or histories or indeed any form of writing. Each chapter covers a period of time but identifies a series of individuals, to anchor broad periods of time in lived lives. This is anything but a dusty history book. Chapter six covers 2000-2020 and the reader is confronted with stark realities that otherwise may have floated by as news headlines among others: 2000-2020: Human Rights, Forced Migration, the 52/48 Brexit Vote, Grenfell Tower, Windrush II and Knife Crime. https://blackbritishwriting.com

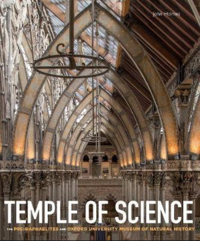

Other books to mention this month include alumnus John Holmes’ Temple of Science: The Pre-Raphaelites and Oxford University Museum of Natural History. The beautiful volume is far more than its title suggests, no less than a distilled narrative of the intellectual and cultural spirit of the nineteenth century seen through the very Oxford business of putting up a ‘temple to knowledge’ that would ape the gothic revival and keep the church faction at bay while quietly but rapidly furthering scientific knowledge to an Enlightenment recipe. Sir Henry Acland sold the idea of learning more about nature as the second book of God, and the University paid for the building which was constructed in the 1850s at a prodigious speed. By the time the cat was truly out of the bag – truly by the 1890s but not forgetting the infamous evolution debate of 1860 held between Wilberforce and Huxley – some of the earlier supporters withdrew their support having noticed that science was turning out to be godless and cold-eyed. John Ruskin was the central figure here and he was enraged.

Four other books to note this month. Merton College Library: An Illustrated History by Julia C. Walworth, the Fellow Librarian at Merton. This is a delightfully approachable book, copiously and imaginatively illustrated and written for all. The celebrated college library has been in continuous use for longer than any other, the college founded in 1264. The most pertinent words in the entire book: ‘It did not survive by chance.’

Alumnus Nicholas McDowell (Oriel, 1994) has written Poet of Revolution, The Making of John Milton which is being described as a massive achievement – a fresh intellectual biography of Milton full of fresh and revealing evidence.

Then conjure an intellectual strand for our COVID times – Greed is Dead: Politics After Individualism by Professor Paul Collier and St John’s fellow and well-known economist John Kay. It is part a manifesto and part an observation, with acute commentary on Brexit, inequality, the utter wrongness of much that passes for economic orthodoxy and the importance of place.

That leads to the final volume for this month – Darkness by Design: The Hidden Power in Global Capital Markets by another fellow of St John’s College, Professor Walter Mattli. Mattli might as well have been talking over the soup to Kay and Ovenden, and we hope he did: the book brings together issues of knowledge, technology in the form of high-speed algorithmic trading in stock exchanges, power, influence and access. The result is a deeply disturbing corruption of what once resembled transparency and fairness. The losers are an unsuspecting public.