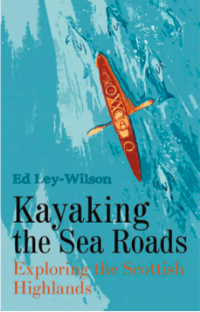

KAYAKING THE SEA ROADS

KAYAKING THE SEAROADS

Alumnus Ed Ley-Wilson heads out into the Scottish Highlands on a kayak…here’s what he learned.

Published: 29 January 2024

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Kayaking the Sea Roads – exploring the Scottish Highlands’ by Ed Ley-Wilson (Whittles Publishing, 2023)

Ed (Harris Manchester, 1994) came to Oxford as a mature student, having already had a career working outdoors all day at sea on Scottish fish farms. A native of the Scottish Highlands and long time resident of Inverness, he recalls standing on a genteel punt and wondering, ‘Oh my word what have I done?’

But Oxford was a success, he says, and his degree in anthropology was prefaced a few years earlier by exploration in the Himalayas resulting in a book, and has evidently informed everything since, including this brand new book Kayaking the Sea Roads.

The new book is a true journey of discovery, combining the adventure story of kayaking 56 days alone up Scotland’s west coast (see map, below left) and a broader investigation of personal and political issues relevant to the area.

Partly inspiring Ed’s trip was a journey undertaken in 1934 by the then future editor of The Scotsman newspaper, Alastair Dunnet, and his friend Seamus Adam. They set off in heavy wooden canoes from the mouth of the Clyde to paddle their way towards a commentary on the social and political state of the Highlands as it was between the wars.

Ed kayaked in their wake, revisiting some of the same themes. Land ownership and community lie right at the heart of both journeys. He can draw on personal memory here, recalling the 1992 meeting when he attended that meeting in Stoer village hall, when the Assynt Crofters stated their intent to purchase the Assynt estate, thereby sweeping away centuries of feudalism in one remarkable act.

He also encounters rampant rhododendrons in Argyll that have ignited a pressure cooker debate about ‘non-native’ species, plus myriad other flash points around tourism (too much of a good thing?) and whether or not to make the Isle of Skye a National Park; environmental issues including the eternal tension around fish stocks; and then perhaps above all for Ed, the sector he has worked in for most of his life, fish farming.

Attentive to that huge and gnawing Highland question of all ages, how do the jobs come and stay and generate sustainable incomes that sustain new families and the schools and shops and surgeries and churches around them? Ed replies that fish farming has been a major and mostly positive answer over the past half century.

It began with five metre-square pens holding maybe 150-fish, an extension of crofting in the late 1960s/70s, a rudimentary means of extending a barely sustainable income from small-holdings and agriculture.

Ed says that the industry took off more rapidly when ‘the big money came’ in the 1990s and noughties, and the industry learned from Norway, expanding at times too quickly with periodic scandals around disease and pollution.

But this is an industry that learns from its mistakes, he says, it has to. There is no subsidy to cover errors of management or lost stock, and innovation is key. With ongoing research from Scottish Universities matched with an ever more robust ethics and sustainability agenda required by UK retail, Ed’s experience is of a farming community that demonstrates the ambition to achieve sustainability. There is still work to do, he says, but the intent is there. Supporting both a knowledge economy and well-paid year-round jobs, the industry is innovating its way both onto land and further offshore.

‘I have both kayaked by and visited on a professional basis, the farm site of East of Skelwick off Westray in the Orkney archipelago. This is one place where the future of offshore farms is being tested. Two kilometres offshore, it has to retain its integrity even with occasional nine metre swells in a winter storm – if you were to lose your fish you would not only lose your livelihood but quite probably your licence too.’

The scale of such pens is vast and even with anything between 15,000 and 30,000 fish in each, this is still only around 5% of the total volume of water in the pen.

The sector involves academic understanding of fish biology and life cycles and feedstocks, on one hand, and engineering derived as much from the oil industry, he says, than from off-shore wind on the other. Indeed, the Norwegians and the Chinese are currently experimenting with using oil rigs as a template for a new breed of fish pen.

The subject remains controversial to some activists who maintain that large scale fish farming is not sustainable in any true sense and does damage to wild fish stocks and the marine environment.

Ed’s position is less negative, and he argues that fish farming has matured into a strong sector and has provided a welcome balancing act to a still-poor agricultural sector and other ‘increasingly controversial’ so-called traditional alternatives for Highland income such as dedicating swathes of moor to grouse shooting or deer stalking.

‘Energy flows where attention goes,’ he says, ‘and there is always a tension between environment impact and social and economic development in any industry’. The trick is to find ways to minimise that impact and create a positive direction of travel.

‘Out here on the far western edge of Europe where resources are widely spread and difficult to access, innovation and resilience go hand in hand’.

What’s the most pressing problem he encounters in the book? The answer is deeply ironic because it involves money moving into the Highlands rather than leaking out. However this is in the form of second homes owned by non-residents, the echo of which will be loudly received in Cornwall and even bits of Oxfordshire, where in some villages no shop can exist and no school can sustain itself, so many of the homes lying empty until the Air B’nB cycle kicks in or their affluent owners decide to pay a brief visit.

Ed advocates that much as in Norway, there should be a stiff residency requirement for such second homes.

Ed made his two month adventure in June and July of 2022, a year in which there was wind and incessant rain – and conditions were not propitious much of the time.

Some of the photos reflect this. The light is the light of summer and therefore magic, but it rarely looks warm and in every sky lurks the next cloudburst.

You could hang the whole book on the Emily Dickinson quote in a chapter called Uncertainty, ‘A coming as of Hosts was heard that was indeed the rain…’ That day the wind blew Force 6+ and Ed was restricted to camp. Under his diary entry for ‘Events’ he wrote, ‘Time in this quiet place. Taking time to watch and listen. Then, under the entry for ‘Camping’, a terse ‘Bothy again’.

But Ed argues without hesitation that the trip was made better by its unanticipated adversity, and he says that instead of finding solace in his phone, when finally sheltering in his tent after a an invisible dividing line between ‘phone to hand’ and ‘free of the damn thing’ and reports that it set his mind free in the most powerful and perhaps unexpected way.

He refers to the concept of ‘the extended mind’ as relating to the value of being out of doors. ‘There is more complexity in a natural environment than a built one, more natural stimulation in being outdoors than being indoors or in your ‘phone universe’,’ he suggests. ‘And yet, despite such complexity, the mind settles, the creative juices start to flow’ and ‘being in the moment’ becomes possible where before it was not.’

This will resonate with some readers and provoke the curiosity of others, the inverse relation between phone use and creativity, switching off to switch on.

In practice, he found that, much as with Henry David Thoreau, whose writing he loves, ‘wonderful things happen when you release your mind from endless world news and start to live in the moment.’ Like an epic yoga class (one of Ed’s other activities) – he found himself in a state of curiosity, veneration, self-exploration and plain good old-fashioned observation.

You can only do this effectively, he says, by making a very deliberate and conscious decision to ‘award yourself the time.’ This can apply to half an hour set aside for a walk, within a working day, it does not have to be a 56-day long epic kayaking adventure.

There was no plan for a book from the trip, he says. He just wanted to journey to a basic itinerary, move with mother nature rather than against her, and take time to think. The journal keeping was almost an afterthought.

‘What was interesting though was that in the writing space I created, very little of what I wrote down needed to be crossed out. After just a few days, ideas began to crystalise and the writing just began to flow. I had a lively clarity.’

The book came out of the experience, rather than the experience being slavishly created to serve a book.

Ed is fully informed of the environmental trammels – pollution, plastics, climate, over-fishing. It quickly runs to academic research and journal articles about salinity and sea temperature. We touch on these.

Yet within his actual adventure, he says that he ‘took great heart’ from the bustling life forms that being in nature sent his way on a daily basis. Birds, otters, seals, porpoises and dolphins were regular companions and he even captured fighting sea otters on camera, from his kayak. The book has beautiful photos throughout, ranging from exotically colourful sedums growing in nooks and crannies, to atmospheric seascapes, original artwork and excellent maps.

There is a lessons-learned section towards the end about re-conceiving ‘sacrifice’ as ‘investment’, a broader debate about giving and taking from nature and what might be a more sustainable way of living within this one world we have.

But the essence of the book speaks for itself. The intensity of connecting with nature in all its glory is wonderfully expressed. Exposed and vulnerable and, in Ed’s case, alone within a vastness of sea and landscape off the west Highlands, this is writing that says to us all, ‘get up off the couch, put away your mobile phone and get out there when you can to rediscover the wonder of our wilder places.

‘Unless you are out there watching, listening, experiencing first hand the birds, animals and plants then our feeling for them is dulled. Out there, beyond our urban living spaces, these fellow souls with whom we share this planet are all doing their thing, quietly and without fuss. Your kayak slips equally quietly through the water and, for a moment at least, you can share their space and live, just for a while, a little differently from the everyday.’

Kayaking the Sea Roads – exploring the Scottish Highlands’ by Ed Ley-Wilson (Whittles Publishing, 2023).

Images by Ed Ley-Wilson; except for Fish farm salmon round nets in natural environment Loch Fyne Arygll and Bute Scotland (GETTY Images).