FAIR PLAY AS NATIONAL CHARACTER – THE BRITISH CASE EXAMINED

FAIR PLAY AS NATIONAL CHARACTER – THE BRITISH CASE EXAMINED

Alumnus Jonathan Duke-Evans has written an extensive history of a cultural idea, but what exactly does it mean?

Published: 25 January 2023

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

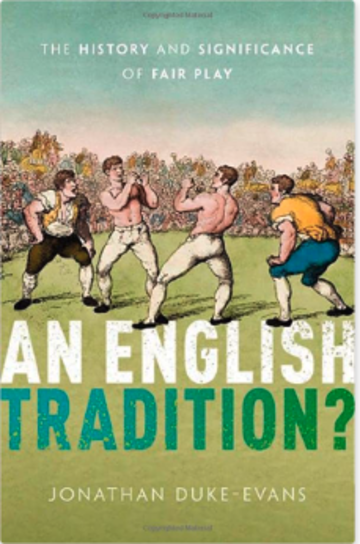

An English Tradition? The History and Significance of Fair Play by Jonathan Duke-Evans (OUP 2023, £35)

A review in one of the national dailies noted that Jonathan Duke-Evans’ (St John’s, 1974) 444-page history of fair play as a feature of the English make-up is in fact a superb read. Perhaps this is a subtle way of confirming that not all academic trade books are quite so approachable, but it prompts Jonathan to emphasise that there is a core of theory behind the anecdotes.

“When I started thinking about what fair play means to us, around twenty years ago, I was ready to go where the evidence led me” he says. “I’d have been quite prepared to debunk the idea that there’s anything specifically English, or British for that matter, about it if that’s what the sources had suggested to me”.

But when the research began in earnest in 2017, following Jonathan’s career as a civil servant, he plumbed numerous databases to find out exactly what people through the ages have meant what they talked about fair play. What he discovered, he says, was that the idea of fair play is linked to the British experience in some deep and unexpected ways.

“I found that the core idea goes back a long, long way. There is a passage in Beowulf where the heroes are preparing themselves for another of Grendel’s murderous attacks on their hall. Beowulf resolves to take on the monster in single combat, and he tells his comrades that he will not use his sword: Grendel doesn’t have one, and we must fight on equal terms”.

Fighting in its various forms crops up all over the book. For hundreds of years Englishmen settled their disputes with their fists while their friends and neighbours formed a ring and enjoyed the spectacle. It was a normal way to end a dispute, but there were rules which we find again and again across the centuries: no ganging up, no concealed weapons, and above all no hitting a man when he’s down.

Some hundreds of years after Beowulf, says Jonathan, you can see ideas about what we call fair play emerging in the common law. The right to a fair trial, the “innocent until proved guilty” rule, the writ of habeas corpus, the reluctance to use torture, the reliance on juries, the security of the home: all these were linked by contemporaries with the idea of fairness. But what made England distinctive in this way?

“Fair play implies reciprocality”, he says. “It’s not just benevolence and it’s not the same as pity. It implies that individuals recognise that they have claims on others to respect them, irrespective of their social status or wealth. It seems to me that in England in the Middle Ages and afterwards you have lower social barriers between the nobility, the gentry, and at least the wealthier peasants than you have anywhere else in western Europe. The fair play tradition is strongly linked with this”.

In spite of that, he’s the first to point out inconsistencies where they occur. Of course the story is messy. Take the case of Robin Hood, who’s a proud yeoman who thinks he’s every bit as good as the knights and sheriffs he encounters, and insists on fighting on equal terms. The real Robin seems to have been a pastiche of different fugitives, and probably none of them were particularly admirable. Even the legendary Robin in his early incarnations had some nasty deeds to account for, like castrating monks to stop them breaking their vows of chastity. I don’t remember that scene being included in the Clannad-themed ITV series that some of us grew up on in the mid-1980s!

“But”, insists Jonathan, “though Robin Hood’s image changes over time, there’s always immense emphasis on his love of a fair fight. And the fact that he was a yeoman standing up to the highest in the land tells us a lot about the heroes that the English chose for themselves”.

I’m already wanting to hear about the implied contrast with foreigners as a way of checking on these claims about the English. But Jonathan is ultra-cautious as one might expect. There’s no monopoly on fairness, and he’s the first to point it out. The ancient Romans had strong ideas about fairness in their chariot races, and the idea of chivalry – a French creation – required knights to fight honourably. The bushido code looked very similar, at least at first glance. But it was in England, and because of the distinctiveness of English society, says Jonathan, that the code of chivalry was first applied to people below the rank of the knights and their ladies.

America offers some interesting points of contrast, he says. The very word “underdog” is American, originally meaning the less fancied animal in a staged fight. And the modern super-hero genre owes a very great deal to the idea of chivalry, popularised in much the same way as in England. But when Americans visualise themselves, they tend to think less about fair play and more about readiness to grasp opportunity – the American dream. The ideas may overlap but they’re not the same.

I ask too about the critics of fair play. Machiavelli, says Jonathan, was the world’s most influential exponent of the idea that fair play gets you nowhere. Putin is not on the list currently for fair fighting: he’s in a long tradition of people who believe that the interests of the state, or the race, mean everything, fairness to the individual nothing.

But doesn’t all this talk of British fair play (and after looking at the evidence Jonathan concludes that we should be talking about it is British, not just English) cover up the inequalities of our own society? Isn’t it a sort of myth we tell ourselves to patch over the ghastly reality? Jonathan’s view is that it’s much more than that. From the Enlightenment onwards, he says, we can trace the process by which the circle of people who have the right to fair play widens – the poor, women, migrants. And so far from being a myth that suits the interests of the ruling class, it was more deep-seated among ordinary people than we might assume, and not only when they fought each other.

He gives the example of team games, often assumed to have been violent free-for-alls before the public school gentlemen of the 19th century took them in hand and drew up the rules. Not so, he says. One of the early versions of football was the Cornish game of hurling. A description of the game from around 1600 makes clear that there were already equal sides and a kind of offside rule. Cricket too was a game of working men in the south of England which was colonised by aristocrats, not invented by them. There was a long tradition embodied by people like C B Fry and the Corinthians that suggested that amateurism was essential to the spirit of sport. But it was amateurs who precipitated one of the bitterest sporting controversies of all time, the Bodyline bowling crisis.

For all that, Jonathan concedes, in modern daily life social experiments suggest that the British are not much more likely to behave honestly than other people when we think we can get away with it. We value fair play in sport, we demand it in our institutions, but we all too often have a blind spot about it in everyday life.

I’m still a bit wary about some of the arguments, but I’m persuaded that national character does amount to something despite all the pitfalls of definition and generalisation. Jonathan gave me an example I liked. In England every neutral roots for the underdog when a minnow gets paired with one of the big fish in the FA Cup. In the French equivalent, back in 2000, Calais Racing Union astonished the nation by winning through to the final from one of the very lowest tiers of French football. “And I’m sure the whole country will be cheering Calais on?” asked one English pundit to a distinguished French player. “Ah non” was the reply. “All this creates disorder…”.

There are plenty of big questions about who we are as a nation to chew on here. To make your own mind up you’ll have to read the book – a highly enjoyable process, while the book itself is beautifully presented by OUP, with the cover adorned by a fearsome pair of prizefighters slugging it out at Moulsey Hurst back in 1810.

Jonathan has an Oxford DPhil in History, with a study of radical political theory in the 18th century. He also has a Master’s Degree from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He made his career in the Civil Service. This is his first book.