WHAT DOES BREXIT REALLY MEAN?

WHAT DOES BREXIT REALLY MEAN?

It's the final convulsion of empire, say two Oxford academics

Published: 24 January 2019

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

What does Brexit really mean? While history is being made in parliament and government and media headlines, far beneath the noisy surface lie deeper currents of meaning.

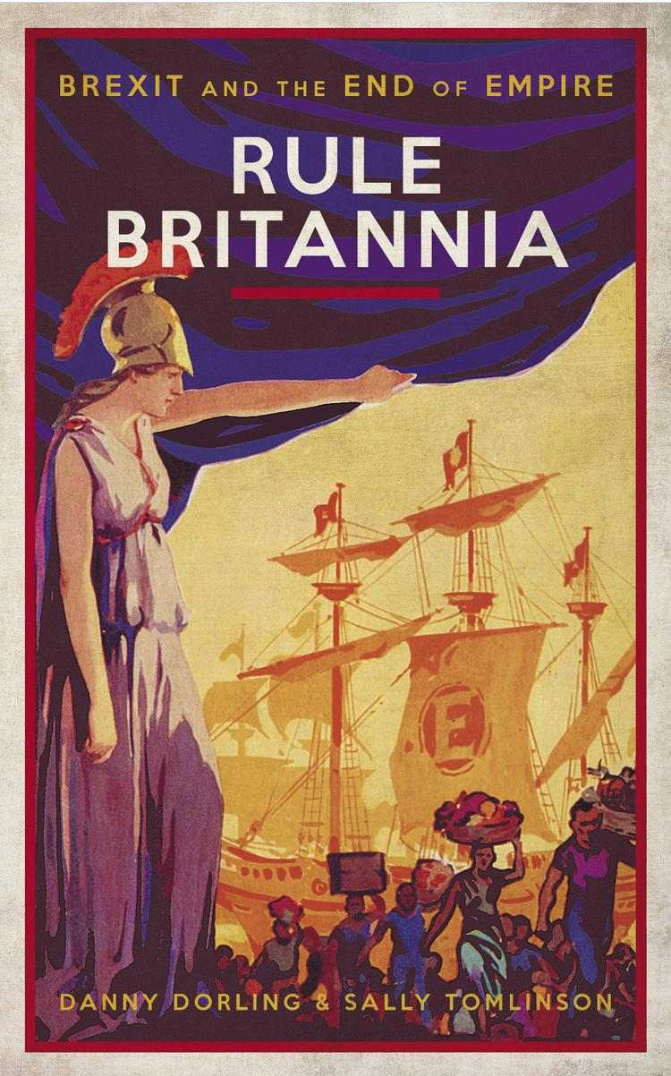

Among the first ‘serious’ analyses is this book, Rule Britannia, Brexit and the End of Empire, by Professors Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson. Sally is an Honorary Research Fellow in Oxford’s Department of Education and Emeritus Professor of Education Policy, Goldsmiths; Danny the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography of the School of Geography and the Environment.

Credit: Biteback books

Danny estimates that perhaps 300 Brexit books have been published since the Referendum vote on June 23, 2016. But most of these were rapid-fire and journalistic. They were shoot-from-the-hip responses to current affairs.

‘While everyone is now saying they are sick of Brexit,’ says Danny, ‘understanding it has hardly begun.’ He estimates that the Brexit equivalent of economist John K. Galbraith’s bestseller, The Great Crash, 1929, published in 1955, will take a similar span of time to appear – in other words at least a quarter of a century after whatever may happen on March 29th, 2019.

Evidence of public hunger, not to say raging thirst, for something other than tabloid coverage, might be discernable from the fact that the first, 2,500 printing of this book, was sold out in less than a week before any major review had even been published.

But it’s never too early to punch out a considered thesis and while both authors here let rip in places, from a leftwing agenda which they freely admit, there is so much carefully weighed analysis and learning that the book may become a classic opening boom in the literary Brexit wars that will now rage for years to come. The book concerns inequality in the UK, and how it has grown steeply since the 1970s; it concerns the geography of the Referendum vote in 2016; it concerns the education system of the UK, and inevitably class; and it concerns the imperial roots of Brexit.

In particular, jumping right in, there is an absolutely blistering Chapter 7 in which the authors take a look at the cabinet around David Cameron, Prime Minister 2010-16; and then also at other Brexiteers and the succeeding Conservative government under Theresa May.

Besides her affiliation with the Department of Education in Oxford, Professor Sally Tomlinson is also Emeritus Professor of Education Policy, Goldsmiths

Credit: Sally Tomlinson

Chapter 7 is called ‘Imperially rooted education and bigotry’. So scathing is the appraisal of Tory ministers since 2010, that it’s too easy to forget that over two-thirds of Cameron’s Cabinet were Remainers; and most who succeeded them Brexiteers at least in name.

But it doesn’t matter that much. The deeper current here is that they have been essentially self-serving. Of the 29 members of Cameron’s Cabinet in 2012, 18 were millionaires or multi-millionaires. The Eton to Bullingdon Club imagery is evoked once more, partly to make the point that these leaders were typically privileged products of private school education, and wealthy enough to be insulated from the financial concerns of most ordinary voters.

Subjected to deeper scrutiny, these various factors point to nostalgia and myth-making about the British imperial past and British self-identity in light of its former Empire. The sole UKIP MP during the referendum was Douglas Carswell. He was raised in Uganda. Arron Banks, who bankrolled UKIP and the xenophobic Leave.EU, spent his childhood in South Africa, where his father ran sugar estates. A subsequent head of UKIP, Henry Bolton, was born and partly raised in Kenya.

Danny's Chair is named in honour of the acknowledged 'father of geography' Halford Mackinder, 1861-1947, who at the end of his life thoguht that Britain would henceforth be a 'moated aerodrome' for US interests. He understood already that the British Empire was at a close.

The authors submit with an astonishing fluency, the thesis that virtually all the key promoters of Leave were operating to a powerful but false idea that Britain could once again be Top Dog, and that the map might once more be painted pink. Boris Johnson is only excluded from this thesis to the degree that he was the most self-serving of the lot, equivocating only in respect of political calculation. But he too owns the imperial outlook, more than most and not excluding his Rudyard Kipling moment, alluded to here lest anyone should forget.

Right at the other end of the educational spectrum, the authors drill down into the UK curriculum and find lots of daft stuff about how we were all Anglo-Saxon once, Primary Schools failing to declare to their young pupils that both Angles and Saxons were German tribes and thus themselves immigrants.

There is a wonderful if inadvertently dry wit to the book. Chapter 2, ‘Britain’s Immigrant Origins’, jumps in by reminding readers that many Britons were slaves of the Romans, the Vikings and the Danes; then vassals of feudal Normans. The last line of Rule Britannia, ‘Britain never ever ever will be slaves,’ is historically-speaking, nonsense.

Old illustration of Eight Mile Bridge (Baliqiao) after battle between Anglo-French forces and China during second Opium war. By Bayrad after sketch of Vaumort, publ. on Le Tour du Monde, Paris, 1864.

At the dawn of the British Empire, ‘British emigrants began invading other countries – though of course they never saw themselves as immigrants when they did so.’ They didn’t go abroad in search of benefits cheques. They went with guns and looted whatever they wanted – the substance of Chapter 3.

The book exudes immense energy and is a rollicking broadside against the Brexit/Tory establishment and the remnant of UKIP. So much so is this the case that it can be compared to Guilty Men, the book rushed into publication under a pseudonym by three anti-appeasement politicians, one a young Michael Foot, in June 1940, castigating the Tory government of the 1930s under Neville Chamberlain.

A taste of this is how the present authors trace David Cameron’s family wealth back to slavery, and you don’t have to be a Guardian reader to enjoy the ride.

Danny admits it; writing simultaneously about history, voting statistics and current affairs that changed by the day as the book was drafted, in some ways shaped the book. ‘It was better to have a point of view than to disguise what that was.’

Isn’t there a vast irony about being the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography and the Environment at the University of Empire, AKA Oxford? The authors own their blushes, in one place noting with a barely concealed merriment, how one of them lives in a Cotswold village that was firmly Leave despite having no immigrants.

In fact Chapter 1, ‘Why Brexit?’ says that this weird, inverse correlation between leavers and immigrants was everywhere in the actual Referendum vote in 2016.

Communities with no immigrants voted Leave. Communities with many immigrants voted Remain. Who voted what did not align with deprivation. Numerically, the most Leave votes were from the south. Some very poor areas in London, Liverpool and Manchester voted to Remain, while the most Leave-voting county was wealthy Essex.

‘On the night of the vote,’ says Danny, ‘the TV journalists beamed in on a blonde-haired woman and two balding men in Sunderland. They had to generate an on-the-spot narrative and that was what stuck – that it was feckless, poor northerners. But it wasn’t. Ground central for Brexit was Winchester.’

Rather than plot-spoiling, the issue of the strong positive correlation between being overweight and voting leave is a fascinating one and it comes back in the book more than once. Correlation is definitely not causation but something is going on here, say the authors, not indistinct from the subjective feeling of many (middle class) leave voters that they had done poorly in their financial circumstances compared to peers in the same, middle class. Widespread knowledge of how rich bankers had become relative to almost everyone else kindled barely suppressed fury. ‘The exit poll had revealed that most leave voters were middle class.’

Too many immigrants became the catch-all explanation, screamed out day after day by the Daily Mail, Daily Express, Daily Telegraph and The Sun, the four leading pro-Brexit newspapers.

Danny says, ‘I am confident that we have established the basic geography of the vote.’

Leave won by just 1.3 million votes. 13 million voters didn’t vote, while 7 million eligible adults were not even registered, disproportionately the young and the transient, the same people most likely to have voted Remain.

For now, and however Brexit turns out, it’s going to be a harsh reality check. ‘But there was never a British nation or a ‘Great Britain’ before empire; it was a cold, damp, backward, unimportant archipelago.’ Welcome home.

The authors are less strong on the defects of the EU and the current UK Labour Party, although they do acknowledge these elements. In fairness that’s not their point and they don’t claim so. Brexit is a British peculiarity viewed from outside the UK. We did it to ourselves. Why? In so many ways the authors answer their own question: it’s time to bury the imperial ghost. We’re not ‘Great’. We’d be much greater if we were just ‘normal.’

What’s ‘normal’? I ask. Danny replies, ‘I’d like to think that our infant mortality rate could be better than the bottom five countries in the EU28. That’s a real aspiration isn’t it?’

Both at the University of Oxford, Sally Tomlinson is an Honorary Research Fellow, Department of Education and Danny Dorling is Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography of the School of Geography and the Environment. Rule Britannia, Brexit and the End of Empire, was published by BiteBack Books on January 15th, 2019, the same day that the government received the greatest defeat in Parliamentary history, 230 votes.

FREE EVENT: Danny and Sally will speak about the subject of their book at St Peter’s College, Oxford, on Tue, 29 January 2019 18:00 – 19:30, and the event is free and open to all. Register through Eventbrite.