SEARCHING FOR ISAIAH BERLIN

Credit: The Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust

SEARCHING FOR ISAIAH BERLIN

November's Book of the Month

Published: 7 November 2018

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

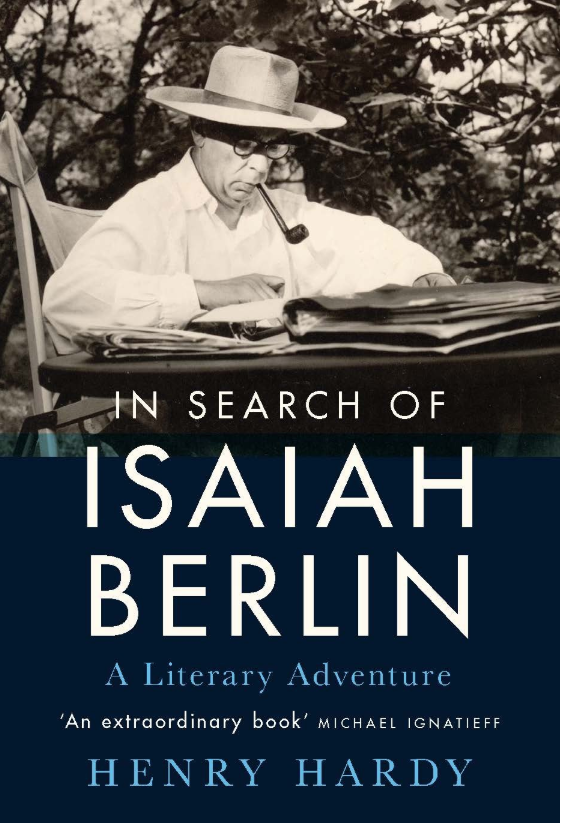

The man who knows the work and mind of famous Oxford intellectual historian Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997), Henry Hardy, launched on October 30th In Search of Isaiah Berlin: A Literary Adventure (IB Tauris, 2018, £20). The launch event, hosted by the Wolfson-based Oxford Centre for Life Writing at Wolfson College, was fittingly held at the very college Isaiah founded and was the first President of, and where Hardy is a fellow.

Credit: IB Tauris

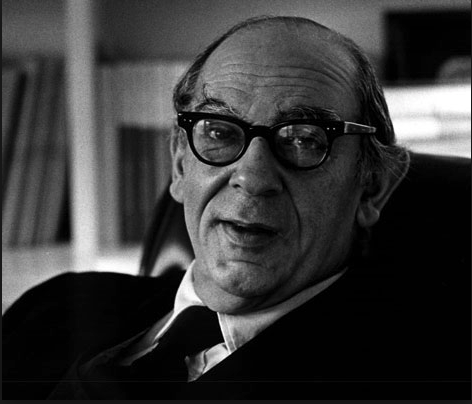

This is no ordinary literary collaboration. Sir Isaiah was famously loquacious in company, sparkling and brilliant and generous-spirited. The downside was that he published little. He needed an impresario and Henry appeared as a graduate student in the 1970s. Beginning then, and since 1990 working full time, Hardy has coaxed into life eighteen volumes plus a four-volume edition of letters, representing a mammoth workload.

The theme of the launch event was Hardy’s memory of descending the stairs into the ample cellar of Berlin’s beautiful house in Headington, to find a ‘ramshackle cornucopia’ of papers. Running with the notion of ‘below stairs’, Hardy compared himself to a sort of Jeeves to Berlin’s Bertie Wooster, but with a frankness present in a cited seventeenth-century French quotation: ‘There are no heroes for manservants.’

On that basis, not all the intellectual knots are smoothed out in this volume. That recommends it immediately, but not only because no one wants empty hero-worship. Instead, the knots are elucidated for contemplation, with numerous letters between Hardy and Berlin deftly drawn on as evidence.

Credit: Wolfson College

Gradually, one sees that the knots are not to be straightened because they cannot be. Rather, everything to do with humans is crooked, as in Kant’s note, ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made.’ No wonder that this inspired the title of one of Berlin’s books, with some coaxing by Hardy.

At the very centre is Berlin’s irreducible conviction that humans possess free will. With that comes plurality and uncertainty in human affairs. Hardy wanted, and wants, Berlin to be a bit harsher on universal religions that do not admit the same plurality, but Berlin was hung up on this, Hardy says.

Hardy was once an atheist churchwarden in Oxford, until removed by the then Archdeacon of Oxford. Equivalent but different intellectual tensions, writ large, become the defining trait, even the celebration, worn on the sleeve, of Berlin’s outlook, which was nonetheless unswervingly committed to empiricism and not to mystery or metaphysics.

Why didn’t Berlin leave behind a school of thought in Oxford? Hardy offered his audience that Isaiah was less complete as a scholar than some peers (Professor Quentin Skinner was mentioned) but abundantly ‘lived’ his philosophy and was to that degree a remarkable, indeed exceptional, human being.

The rest of the answer may have something to do with Oxford. While drawn to what Hardy describes as the ‘no-nonsense English temperament’ and the ‘dry light of Oxford philosophy’, Berlin neither lived nor wrote like them. You can argue thus that his greatest strength was to be a continental thinker in a damp English setting. He set the Cherwell on fire even though it wouldn’t burn. It’s not a skill set easily handed on.

Once Berlin had turned to history he concerned himself very much with alive ideas, or what he called the ‘hares that are still running’. He wasn’t Kant, piling up words so thickly that all of posterity wouldn’t be able quite to cut through them.

The other reason Berlin left behind no school is that his hinterland was so vast no one could keep up, except perhaps Henry. He was thoroughly at ease with Russian literature, the transatlantic liberal tradition, politics, history and philosophy. He knew the leading (contemporary, living) lights of these subjects, maintaining a vigorous correspondence with them all. In that sense the worldly don.

Nonetheless, Timothy Garton Ash, Professor of European Studies at Oxford, who sat with a distinguished panel on the night of the book launch, declared himself ‘ein Berliner’, and has spearheaded a phenomenal campaign for liberty. Not a school then, but a great affinity.

Credit: The Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust

Sometimes known as 'Government House', this was the home in Headington where Isaiah Berlin lived. The cellar where his papers were found was positioned at the front.

The other towering ex-Oxford figure and direct descendant of Berlin is of course the philosopher John Gray, one of whose early books was recently reissued in a new edition as Isaiah Berlin: An Interpretation of his Thought.

But the essential difficulty of Berlin’s intellectual legacy is why Henry was needed, and this book shows more than any other how fruitful the relationship has been.

The Panel convened in the Haldane Room of Wolfson College was chaired by Robert Cottrell, editor of The Browser. Sitting on the panel beside Henry Hardy was writer and TV producer David Herman, and Timothy Garton Ash, Professor of European Studies at Oxford University.