PURPOSE UNLOCKS PROFIT

PURPOSE UNLOCKS PROFIT

An Oxford professor discusses a blueprint for the reform of Capitalism

Published: 15 January 2020

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

QUAD met Professor Colin Mayer, (Oriel, 1971) to talk about the future of business and a unique programme to rethink capitalism at its profoundest level.

Professor Mayer is Peter Moores Professor of Management Studies, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, but he is also Academic Lead of The Future of the Corporation Programme, led by the British Academy.

The three-year programme is entering its final year with a series of global summits planned to publicise its conclusions, one of them that companies need a clear sense of their purpose in order to justify their existence and solve the pressing needs of society and the environment.

‘The purpose of business is to solve problems profitably, and not to profit from causing or exploiting problems’, says Mayer.

Far from being dull or academic – the very word ‘corporation’ can dull eyelids – the conversation quickly leads to a spirited discussion about the third series of hit US TV series Fargo which in so many ways dramatises financial chicanery that is shown to be both legal and illegal in unexpected ways.

In essence, the plot involves villain V.M. Varga (played by David Thewliss) taking over a steadily profitable, if dull Mid-Western company and then using it as a vehicle for monetary purposes other than what the company was intended for.

‘Capitalism became predatory with the emergence of the ‘hostile takeover’ culture of the 1990s, but the past decade has instead seen the rise of the so-called ‘activist investor’, often a hedge fund or asset manager that buys a block of stock in order to wield influence over the board, to drive typically short-term shareholder value,’ says Mayer.

One of Mayer’s points is not that such activity is invariably wrong but that where it is motivated solely by greed it usually wreaks havoc on the long-term prospects of the company, partly because it loses sight of why the business was there in the first place.

As if prompted by the incidental naming of the TV series, he cites the Wells Fargo bank scandal and the broader ‘hollowing out of the Mid-West’; the case of what happened to aircraft maker Boeing since the effective reverse takeover by McDonnell Douglas; and very recently the case of Peter Polman at Unilever, a man of principles whose planned retirement was apparently accelerated by a briefly-tabled hostile takeover bid by US food giant Kraft Heinz, with unknown long term consequences – although the day before we meet Unilever had unexpectedly shocked analysts and put out a profit warning.

Behind the flotsam of headlines, of course, are deeper issues.

The need for purpose beyond monetary profit is one of the core insights of Professor Mayer’s book Prosperity (OUP 2018), itself the outworking of a paper that elicited enthusiasm among other Academicians and led to the original British Academy involvement, initially under then British Academy President and former Oxford lecturer the economist Lord (Nicholas) Stern (Nuffield, 1968).

Mayer says that 2019 saw ‘a marked change in attitude’ among business leaders – the year of Extinction Rebellion, the year of wider public awareness of environmental issues but also a broader connecting up of dots joining up these issues, some tracing their roots to the financial crash of 2008-9.

The first report Reforming business for the 21st century (November, 2018) argued that ‘the purpose of business is to solve the problems of people and planet profitably, and not profit from causing problems.’ The idea is that individual businesses would then find and declare their own unique purpose, and that the process would be encoded in corporate law.

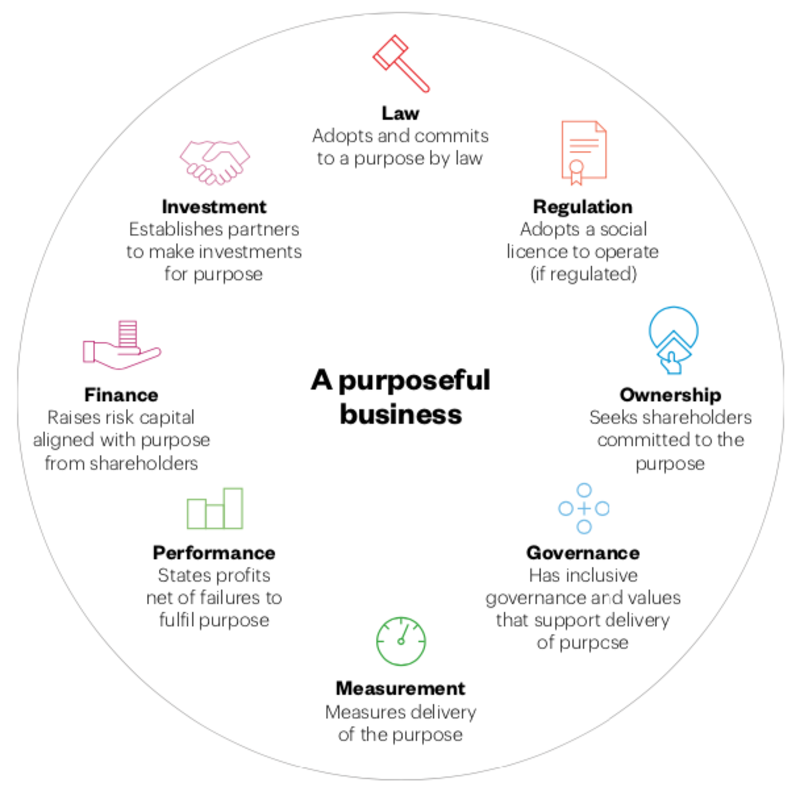

The second report Principles for Purposeful Business How to deliver the framework for the Future of the Corporation, An agenda for business in the 2020s and beyond (November 2019) lays down a framework of solutions in the form of eight principles:

They are:

- Corporate law should place purpose at the heart of the corporation and require directors to state their purposes and demonstrate commitment to them.

- Regulation should expect particularly high duties of engagement, loyalty and care on the part of directors of companies to public interests where they perform important public functions.

- Ownership should recognise obligations of shareholders and engage them in supporting corporate purposes as well as in their rights to derive financial benefit.

- Corporate governance should align managerial interests with companies’ purposes and establish accountability to a range of stakeholders through appropriate board structures. They should determine a set of values necessary to deliver purpose, embedded in their company culture.

- Measurement should recognise impacts and investment by companies in their workers, societies and natural assets both within and outside the firm.

- Performance should be measured against fulfilment of corporate purposes and profits measured net of the costs of achieving them.

- Corporate financing should be of a form and duration that allows companies to fund more engaged and long-term investment in their purposes.

- Corporate investment should be made in partnership with private, public and not-for-profit organisations that contribute towards the fulfilment of corporate purposes.

The media reaction has been extensive. Mayer says that reactions have fallen into three camps:

‘The first says: This is fantastic and just what we all need; the second says ‘all companies have purpose already so the report wasn’t needed’; the third camp seeks to portray it as deluded or politically motivated ideology of the wrong sort, not welcome at all.’

He then says that a great number of people have come back to the first position having given one or both reports a fair hearing.

A third and final report will be published to conclude the programme at the end of 2020.

Oxford colleague Paul Collier’s book The Future of Capitalism is cited by Mayer as another inspiration for the broader British Academy programme. Sir Paul Collier is Professor of Economics and Public Policy in Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government and Director of the International Growth Centre.

In The Future of Capitalism, published in April 2018, Collier offered a mea culpa on behalf of economists who he says became ‘lazy’ about globalisation, believing wrongly that greater efficiencies in economic production would drive greater prosperities for all, even if unequally.

Instead, he argues that globalisation has not been good for all and the ‘bottom billion’ global citizens are often on a ‘down escalator.’ Some of the ‘new anxieties’ of 21st Century Capitalism, as he terms them, extend right across wealthy states too and concern provincial disadvantage and a lack of tertiary education, the latter a prerequisite for getting on the economic ‘up escalator.’

Collier and Mayer agree that there are always solutions when capitalism derails itself, as it did in the 1840s, the 1930s and most recently in 2008-9. The point is to correctly deduce what went wrong and then articulate responses.

But Mayer is also clear that not everything that is wrong with capitalism can be attributed to globalisation. He emphasises instead the ‘financialisation’ of capitalism, which returns the conversation to the earlier theme of companies being impaired by new owners whose principle interest is short term financial benefit.

One of the broad points argued by Mayer is that the era of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) is over.

He is referring roughly to the past sixty years of capitalism, a period of dizzying economic growth in the west, but also one in which shareholder interests became the overriding purpose of corporations.

‘Historically,’ says Mayer, ‘this was never the purpose of a corporation.’

Friedman, a Chicago economist, notoriously argued in a Times magazine article in 1970 that businesses' sole purpose is to generate profit for shareholders, an idea that gained wide traction during the 1980s and beyond.

Mayer argues instead that the purpose of a company is to solve problems that are useful to society, and also that avoid harm to people and to planet.

Asked about companies that might be described as inherently ‘bad’ – say online gambling – he argues that the trickiest propositions create the most interesting challenges.

He mentions ‘addictive product’ categories of company – tobacco is the obvious one, not just gambling and alcohol – and mentions Philip Morris’ attempted reinvention of itself around a ‘smokeless world,’ as it promotes alternatives to traditional tobacco.

Not everyone would see that as much better, but human nature is unchanging and the marketplace provides what customers want, within regulatory structures.

In the case of big oil, he says that the deliberation of true purpose is actually quite straightforward: ‘they are energy companies rather than ‘oil companies’ per se, and as soon as you see this a window opens for them to pivot to non-fossil alternatives…’

Asked about the chances of another big derailment of capitalism, Mayer replies that he doesn’t think it will come from the banking sector, but from the shadow banking sector, by which he means everything from crypto currencies like Bitcoin to peer-to-peer lending organisations – new businesses that are performing some of the functions formerly fulfilled by banks but are not regulated as closely as a bank.

To qualify what he means, Mayer is quick to downplay a kneejerk ‘more regulation is better’ attitude. He cites M-Pesa, a mobile phone-based payment app that rapidly gained acceptance across swathes of Africa starting in Kenya, a striking example of a thoroughly innovative use of technology that helped a lot of ‘unbanked’ people achieve a sudden leap up in economic inclusion.

Nick Read, Vodafone CEO, recently told the Financial Times that he envisaged the fledgling fintech platform now owned by the telecom giant as capable of becoming ‘Africa’s largest unbanked bank.’ (FT Dec 18, p15)

Mayer, who is as optimistic about capitalism’s potential as he is concerned by its failings says, ‘The point here is to pinpoint risk. If there are no regulations but high risk, that is where you get bubbles and failures.’

Image taken from the 2019 report Principles for Purposeful Business, p19