ON THE GALWAN BRAWL AND BORDER DISPUTES IN LADAKH

ON THE GALWAN BRAWL AND BORDER DISPUTES IN LADAKH

Author James Crowden offers a context for recent clashes between China and India

Published: 17 July 2020

Author: James Crowden

Share this article

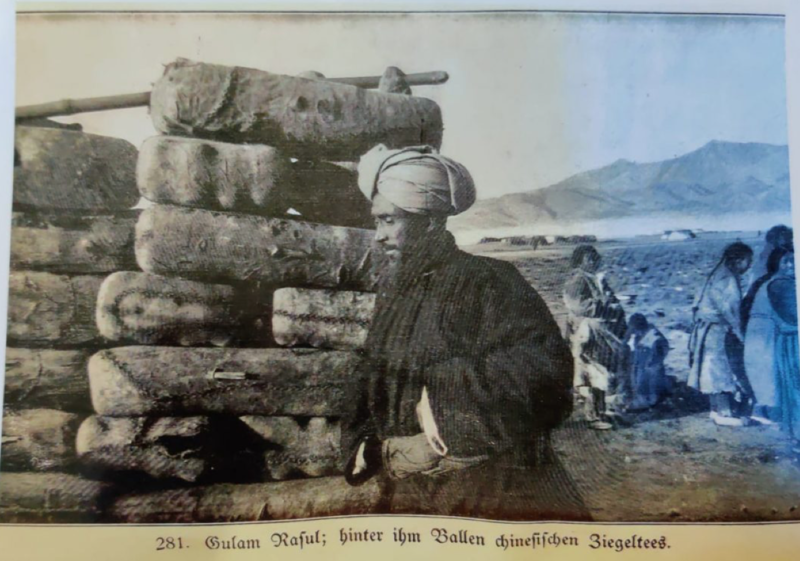

If it wasn’t for the tragic loss of life, the Argy Bargy between India and China in a remote high-altitude valley, could appear like ‘a fight between two bald men over a comb’ - to quote Jorge Luis Borges. Border spats have been going on for years. But this one was different. On the night of 15 June 2020, in Galwan Valley, named after Ghulam Rasool Galwan, a Ladakhi caravan leader and banjo player, soldiers of 16th Bihar Regiment fought three skirmishes in the darkness. Chinese soldiers were armed with rocks and clubs studded with barbed wire and nails. Twenty Indian soldiers were killed, including Colonel Santosh Babu. Seventy were injured. Chinese casualties are not known but 16 Chinese bodies were returned. The brawl was serious.

Stupa in Leh-Ladakh city. The 22,836 sq mile region of Ladakh situated in northern India was made a union territory on Oct 31st, 2019, meaning that it is a federal territory governed directly by the India government.

It goes back to the 1962 Sino-Indian war. The Chinese, after invading Tibet in 1950, sliced off the Aksai Chin, an area a quarter the size of Wales, inhabited only by wild yak, wild donkeys and antelope, with a caravan route connecting Xinkiang with Tibet and Ladakh with Khotan. The Chinese then built a road right across Aksai Chin without the Indians realising it.

In the 17th century Ladakh had sided with Bhutan and fought a war with Tibet. They lost. The Tingmosgang peace treaty of 1684 recognises the ancient boundaries between Ladakh and Tibet going back to the 9th century AD. It refers to trade in tea, wool, gold dust, saffron and cotton cloth. This treaty was respected for over 250 years and the boundaries replicated in the Chushul treaty of 1842 as well as in the MacMahon line and Simla agreement of 1914. China was not on the scene.

Ghulam Rasool Galwan in 1907 with bales of tea destined for Leh photo taken by Sven Hedin. The Galwan River has been occupied by Chinese troops since 1962 and has been a focal poiint of clashes with India.

Credit: Sven Hedin via the author

Before I went to Ladakh in 1976 I consulted Major Peter Hailey, Bursar of St Antony’s College, who had been British Joint Commissioner in Leh in 1939 and was responsible for those eastern boundaries. Peter showed me his maps. I was struck by the word 'UNEXPLORED' which cropped up several times in the Aksai Chin. Peter explained that the Aksai Chin was only used by trading caravans and nomads who moved according to available pasture: yak and pashmena goats. It was a fluid border but well recognised. Common sense dictated by custom. I also contacted Prof Kenneth Mason, Oxford Professor of Geography, at Hertford College. He knew Ladakh and with the Survey of India had charted the Shaksgam Valley which now acts as a buffer between Pakistan and Xinkiang. Porters he said were 8 annas a day. Half a rupee. Mason’s Route Maps of the Western Himalaya 1929 detailing caravan routes over the Karakoram stage by stage are an invaluable source of historical information.

I spoke to Jigme Taring about China’s invasion of Tibet. He reminded me that in the 1950s the UN was fighting a war with China in Korea. No chance of mediation. If India, America or UK had recognised Tibet diplomatically in the gap between 1947/49 things might have been very different.

Indian Army base on the way from Hunder to Nubra valley, Ladakh (2018)

On a more humorous note I spent four weeks with John Cleese and his psychiatrist Robin Skinner in Ladakh in 1990. John twisted his ankle when doing a silly walk at high altitude on top of the Taglang La at 17,400 ft. When I asked him what happened, he simply said, ‘It is a very long way from the Command centre down to the ground’. Maybe that is one reason why these border incidents occur so frequently.

The Indians, (who are also currently entrenched on the Siachen glacier) will be well aware that back in December 1841 the Dogras lost a whole army in Western Tibet, mostly frozen to death, including their General Zorawar Singh. Fighting along the 'Line of actual control' without fire arms is in comparison symbolic and theatrical, but occasionally deadly as at Patrol Point 14. The Indians have now completed their Bailey Bridge but the Chinese have been using bulldozers to divert the Galwan river to gain more ground. Now there is a lull. Talking time.

What next? The Chinese play the long game. For now its army has pulled back troops from Gogra, Hot Springs and the Galwan valley, and significantly thinned down its presence in the ridgeline of "Finger Four" at Pangong Tso. But that doesn’t mean they’ve dropped their ambitions in the region.

James Crowden (Magdalen, 1977) has just published The Frozen River: Seeking Silence in the Himalaya (William Collins, 2020), also reviewed on page 30 of the recent print edition of QUAD.