BOOKS FOR MARCH

BOOKS FOR MARCH

From Cuban economics to Albanian folk music, alumni books for the month...

Published: 3 March 2020

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

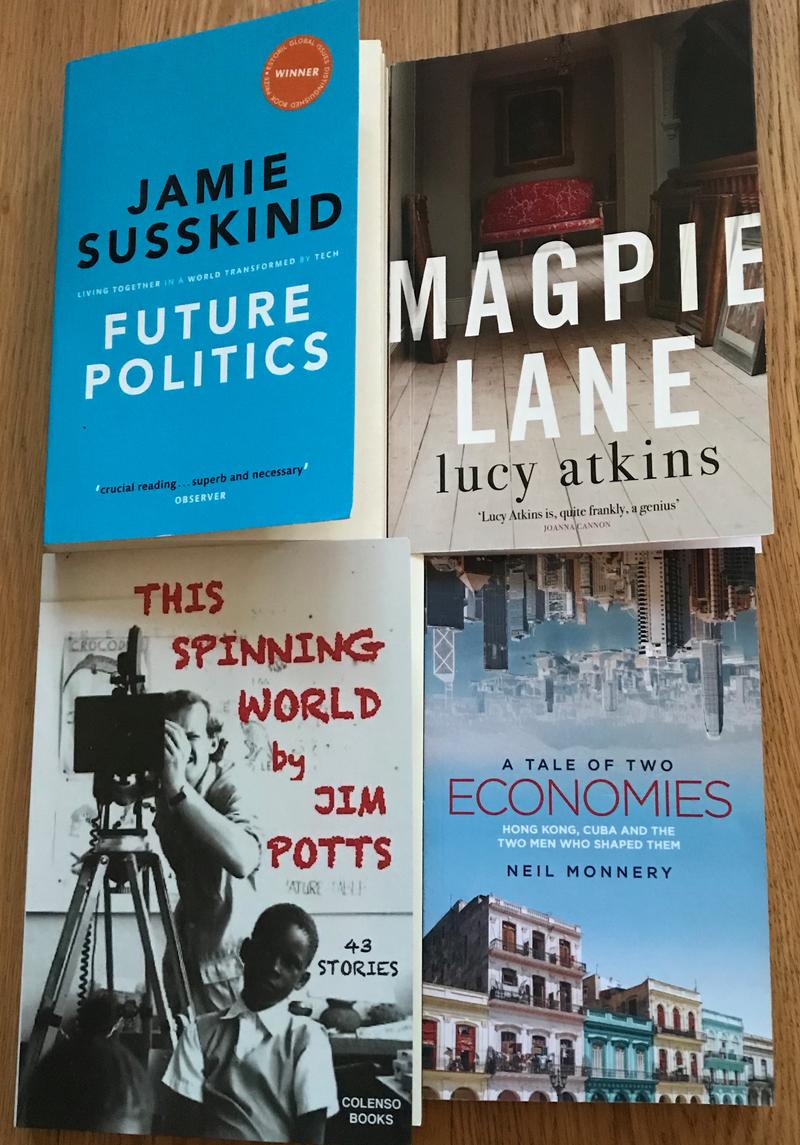

Future Politics: Living together in a world transformed by Tech

by Jamie Susskind, OUP 2020 (paperback), £9.99.

The author (Magdalen, 2007) created a splash when he originally published this work in 2018 and will speak at the 2020 Oxford Literary Festival, March 27-April 5.

While this paperback edition is not much changed from the original save for a new Foreword, the ideas are still fresh.

If the author were to add a new chapter on Corona virus outbreak and containment he would have a fascinating case study for many of his themes; the fact that authoritarian regimes are both better and worse at containing outbreaks and possibly the fact that greater individual liberty isn’t necessarily conducive to freedom in the event that you catch Covid-19 for want of a decent health service.

The book is for ordinary people who want to know about the future; and for politicians who crave some basic explanation around baffling technologies and what they might mean for politics and society.

Its premise is not that we can accurately look into crystal balls, but simply that ‘The future stalks us more closely with each passing day,’ ‘we aren’t ready’, and ‘most of our political ideas were dreamed up to describe a world that no longer exists.’

In all those senses though the book turns out to have a reassuringly familiar feel to anyone who’s studied politics at degree level.

The book is erudite and littered with insightful citations drawn from literature and political thought down the ages; fully 150 pages, or roughly a quarter, is footnotes and indexes. All the underlying ideas are the staples of a PPE course: democracy (what is it?); liberty, freedom, restraint, force, coercion, the state, the individual.

Swirling around though are the spanking new technologies that profoundly affect all the above, with lots of machine learning, artificial intelligence, algorithms and encryption. Many of the illustrative examples of ‘gosh look what happened here!’ rack up a bit like reading an extended version of Metro. Facial recognition except that it can go wrong; treating employees like machines (old and new: the industrial revolution and then Amazon warehouse workers passing out in the heat); scenarios in which drones shoot lazers and paintballs at protesters, and always a reminder that such devices of state control have been manufactured and indeed used, in this case in South Africa.

There are hundreds of examples skilfully deployed and as such, the book tethers itself very carefully to the real and is entertaining too. Only at the very end and mercifully briefly do we get clairvoyance stuff about the singularity (Ray Kurzweil) and Oxford’s Nick Bostrom on machine ‘superintelligence’ by the mid-century that could, he argues, wipe us out as a species.

Climate change isn’t mentioned once which is a conspicuous weakness of all these sorts of books, which seem to go down a rabbit hole defined by David Hume at one end and Karl Marx at the other. It’s much more exciting to envisage being wiped out by a computer a few decades from now than to contend with the annoying fact that we’re already on that path today in 2020.

Several other reviewers have tagged the book ‘shocking’ but I’m not sure I agree. For every progress a new shadow. For every new technology, a new political implication that politicians are rarely able to get their heads around, such as how to tax Apple. If anything this is drearily familiar.

Chapter 7 on Scrutiny is terrific. It led this reviewer to a new understanding of why so much reported mental fragility and anxiety among the population is coming less from overt forms of surveillance of the sorts envisaged by George Orwell, and more from self-scrutiny that comes out of comparison and projection afforded by, say, Instagram or the online version of a tabloid newspaper.

If you are uncertain about who you are (one definition of being young) and spend all day seeking reassurance online, you might quickly become ‘a self-policing subject, a self committed to a relentless self-surveillance.’ While this insight bounces the author straight into Michel Foucault and Jeremy Bentham (Foucauld defined as an intellectual rockstar for those at the back of the class), the point is well taken – ‘the digital lifeworld,’ argues Susskind, ‘will bring about a transformation in the capacity of humans to scrutinize each other.’

Public-private distinctions will be torn down, some of the stuff will sit on servers in a ghastly sort of eternal afterlife; we’ll all be easy prey to predictive codes that’ll know what we want before we have the thought (and they’re usually spot on); and our lives will become metrics he says – rateable and subjected to scores and rankings. None of the above will necessarily be conducive to happiness, which is shocking in its way, perhaps.

There’s not much on cyberwarfare but evidently much of the technology that we already have is supercharging the state, especially the authoritarian state, for which many of the new technologies are a dream come true.

Chapter 17 namechecks Jamie’s brother and father who have written about robots depriving people of the need to work. Once again the thesis is real but the underlying truths are very familiar. No one wants degrading or dangerous forms of work, yet work itself is constitutive of human dignity and meaning. We might have to invent new forms of work. John Maynard Keynes predicted all this a century ago.

Magpie Lane

By Lucy Atkins. Quercus 2020 (hardback) £15.40

This novel has just come out. It’s already had a convincing battery of rave reviews. The author, an award-winning feature journalist and Sunday Times book critic, explores the mystery of the disappearance of the eight-year-old daughter of an Oxford head of house. The copious number of references to the road of the title and other nearby haunts (Deadman’s Walk off Merton Street, for example) leads this reviewer to conclude that the author is imagining the President’s dwelling in Merton Street attached to Corpus Christi College. The author, on further investigation……..attended Corpus, matriculating in 1987! No plot spoilers but Lucy knows Oxford inside and out and no surprise, page 161, the accusation of ‘deep, institutional misogyny. Those old men hated her because she was a young, attractive, pregnant woman without a degree.’ I mention this because it chimes with another snatch referenced below in the book of short stories by Jim Potts. It’s fiction but it’s rooted in a certain truth, hopefully no longer true.

A Tale of Two Economies. Hong Kong, Cuba and the two men who shaped them

By Neil Monnery, Gulielmus Occamus November 2019 (paperback) £15.99

Having previously written dedicatedly about Sir John Cowperthwaite, the author (Exeter, 1980) has written a remarkably enjoyable case study comparing Hong Kong’s success to Cuba’s failure, anchoring some of the narratives in the personalities of Cowperthwaite and Che Guevara, the latter much less well known as the architect of Cuba’s communist economic system.

The author went once to Harvard Business School so you anticipate a slam dunk against those silly Commies. But not a bit of it. The mutual systems and individuals are treated with great respect, and Monnery is alive to contingency: what would you have done in their shoes? Hong Kong narrowly avoided Communism itself, while Cuba’s path was partly determined by the preceding crony capitalism of Battista.

Towards the end this opens up into a wonderfully clear series of notes. The Cuban experiment was much better than its North Korean counterpart, the two systems the only survivors from 40-odd Communist states in the early 1960s. Survival is its own, strange kind of success and in Cuba’s case rested partly on heavy investment in education and healthcare.

China sits apart now as a remarkable experiment in authoritarian politics and free market economics, the outcome unknown.

Meanwhile the Battista ‘crony capitalism’ model has been recycled to various degrees in the west, whether we look at the Trump Presidency or at 82,000 lobbyists in Brussels, 7,000 of which apparently have access to the European Parliament.

Thus the ‘lessons learned’ bit of the book are well handled. Both models have things to teach us.

The author would benefit from reading his Susskind and both would benefit from reading some George Monbiot, if only to remind us that spectacular economic growth is typically at the expense of biodiversity, natural capital and the climate. The climate crisis is the real reason why a moderately performing economy with strong checks and balances – Neil does turn to the Nordic model briefly – might be a more sustainable one over the longer term, in both senses of that word.

There is a luminous detail on page 195. Apparently the current Chancellor of the University, upon handing over Hong Kong to the Chinese in 1997, met Cowperthwaite and reportedly remarked, ‘So, you are the architect of it all.’

This Spinning World

By Jim Potts, Colenso Books 2019 (paperback) £14.99.

What a lovely book. The author (Wadham, 1963) has accumulated 43 short fictional stories encompassing a vast range of topics but with a steady accumulation of niche insights about Albanian folk music, Greek islands and imagined diplomatic underdog heroes who are ‘out there’ trying to find something out, somewhere around the end of the Cold War. My favourite one is called ‘Reward!’ No plot spoilers here but there is perennial awareness of and reference to the mothership, Oxford. Tom, our underdog diplomat hero, recently and painfully returned to chilly London from an exotic posting (the frisson of that so beautifully expressed for alumni who ‘got away,’ only to have to ‘come back’) decides to quit his Pall Mall club to save money. ‘He used the club’s crested notepaper to express his regret that he wished to resign, ‘in order to join another more clubbable club which offered female members full equal rights with the men.’ See the review of Lucy Atkins’ Magpie Lane above. There’s a theme here. The club in question? You can guess. It has Oxford in its name.

*Please note that Jamie Susskind is one of many Oxonian authors and speakers featuring at this year's Oxford Literary Festival

Alumni can claim 20% discount off most sessions (excluding workshops and dinners). Log in to your Oxford Alumni Account to access the discount code.