THE SKELETON ARMY CAME TO OXFORD

THE SKELETON ARMY CAME TO OXFORD

Crime fiction alumna Alis Hawkins talks to QUAD about her latest novel

Published: 29 April 2024

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

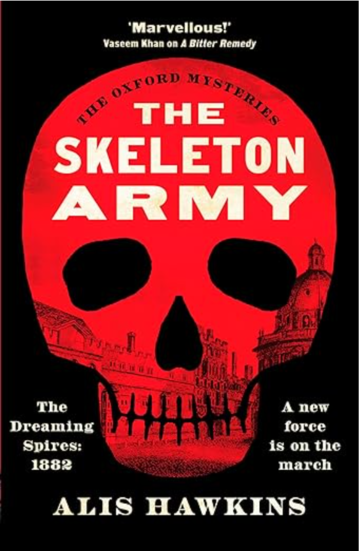

The cover of Alis Hawkins’ (Corpus Christi College, 1981) latest crime novel is a lurid red Radcliffe Square seen through the cut-out of a skull, while the fonts mimic the High Victorian newsprint of 1882, the year in which the story is set.

It’s dramatically successful book jacket, presumably to be duplicated on a paperback edition that comes out in October.

But you almost expect a zombie army and the Stephen King treatment, while actually we’re dealing here with a real historical phenomenon, the brief emergence of an anti-Salvation Army movement in Victorian England, calling itself the ‘skeleton army.’

Alis qualifies that. ‘In truth it was really at its core an anti-temperance movement.’

Anyone at High Table would have presumably approved then, so that’s OK. Pass the claret.

Joking aside, the Skeleton Army was socially about as far away from an Oxford college as you could get, and for the purpose of the novel is based in the parish of St Thomas, known as the brewery quarter.

‘The Skeleton Army started in Weston Supermare, had a presence along the south coast and up as far as London; what is interesting is that I found direct newspaper evidence of its existence in Oxford, and it may have spread further into the Midlands.’

The implication is strangely that there was initially a sympathy between threatened Anglicans who completely disapproved of the loud street marching, raucous singing and young female leaders of a burgeoning Salvation Army, and working classes who frankly resented being told not to drink.

‘We forget just how radical the Salvation Army were. They seriously ruffled feathers, and there may have been a degree of envy as they filled their ‘barracks’ to the rafters with worshippers at a moment when the Anglican establishment worried about dwindling congregations.’

Somewhat less clear is the extent to which the ‘skeleton armies’ were being funded by brewing interests. Alis says that there is definitely some suggestion of that, conceivably also in Oxford where there were multiple brewing families like Marstons.

By the mid-1880s the Salvation Army had been more accepted into the mainstream and its skeleton detractors had also calmed down, so the whole phenomenon was comparatively short lived.

Anyway, immersed in this strangely evocative slice of Oxford, Alis has written a cracking crime novel, the second of a series featuring Rhiannon Non Vaughan, (known as 'Non', a common Welsh treatment) a progressive and boundary bashing female student and aspiring journalist at the very dawn of women actually being allowed to study at Oxford, and a tutor called Basil Rice, who Alis assures us is based on no particular individual but who is in the impossible position of being gay and trying to hide it, which echoes many Oxford lives where sexuality had to remain a very carefully guarded secret.

There is a murder (of course) and the Skeleton Army is under suspicion. Into this wade Non at one end and Basil at the other, with alternative chapters being told from their respective viewpoints.

A reviewer at The Times commented that the mystery is ‘dripping with atmosphere’ but to that we’d add that it always feels plausible.

Alis says she spends half her life immersed in the National Newspaper Archive, today online where once you had to claw up the Northern Line to Colindale and turn the dusty pages or twirl a guider on a microfiche. ‘I spend half my life immersed in it – you pay a fee and then you can search that archive by keyword. It’s amazing…’

A founder of the Welsh crime writers’ collective, Crime Cymru, she says that historical accuracy is terribly important and that she and her fellow members often discuss the matter

‘To the degree that you get a detail wrong, you can undermine the whole novel’ she says.

She reminds me that in 1882 Hertford’s famous, Venice-aping bridge hadn’t been constructed yet. To have referred to the bridge in her narrative, set in 1882, would probably have escaped the notice of most of the audience but not all – and would still be a mistake.

‘Oxford was already conceivably moving towards the ‘twentieth century’ by 1882 – for instance dons had been allowed to marry since 1877. It was changing very rapidly.’

Alis originally studied English at Corpus, and was closer to the Medieval period. ‘I only came into the 19th Century when I wanted to write about the Rebecca Riots, which saw rural dwellers in west Wales, including Pembrokeshire, Cardiganshire, and Carmarthenshire, protest road tolls. Taking place across four years (1839-1843) they were notable for their scale and duration, but also for the lack of attention they got.

‘I really wanted to write about that because the riots happened around where I grew up, and the Rebecca movement represents one of the most sustained periods of civil disobedience in British history and scarcely anyone had written about it.’

The subject led her to four novels before she began the current series with A Bitter Remedy, selected as a Welsh Waterstones Book of the Month in 2023.

Alis says she has had a lifelong fascination with crime fiction and co-founded the Welsh biennial Crime Literature Festival four years ago.

The Skeleton Army by Alis Hawkins (Canelo, April 4, 2024).

Picture credits: GETTY IMAGES LTD.