SURVIVING THE HOLOCAUST

SURVIVING THE HOLOCAUST

A moving memoir of his mother by a former Rhodes Scholar speaks to the world we find ourselves in late in 2023

Published: 18 October 2023

Author: Doron Weber

Share this article

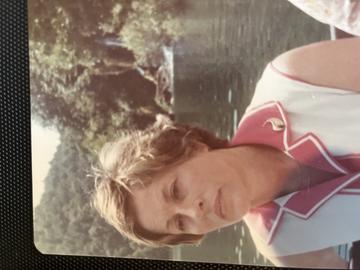

My mother Helga, a Holocaust survivor, died last year at 94 (pictured, above with Doron, right, and below).

She died at home in Rego Park, Queens, in her own bed, surrounded by those who loved her, including her 94-year-old husband and partner of 71 years, Robert.

Despite our wrenching loss, my mother’s long life was a triumph over history and holds lessons for us today regarding fascism, racism, xenophobia, mass delusion and mass murder, and resilience.

Helga was born in Leipzig, Germany in 1927 into a prosperous, middle class Jewish family. The Frenkels lived in a fashionable part of town and her father owned a thriving fur clothing business. A Levite, he took pride in reading the Torah at his synagogue.

Helga was a pretty, 11-year-old girl with vivid blond hair, striking blue eyes and fair skin. One day in the school auditorium, the headmaster brought her to the stage, proclaiming 'See, this is what a pure Aryan looks like!' When Helga boasted to her mother how she had been singled out, her mother slapped Helga and had her transferred to a Jewish school.

My non-stereotype-conforming Jewish mother had been perversely co-opted by a racist ideology.

On 9 November 1938, Kristallnacht 'the night of broken glass,' erupted. Helga could see the black smoke of her burning Jewish school from her house on Springer Strasse. But with a child’s narrow-centered view, she was pleased to get the day off from school and did not grasp its impact.

A violent pogrom often cited as the Holocaust’s launch, Kristallnacht saw ordinary Germans join with Nazi Party members in smashing, plundering, and burning hundreds of Jewish shops, schools, homes, and synagogues. Thousands of Jews were murdered, beaten, or arrested and sent to concentration camps.

On 15 November 1938, only six days after Kristallnacht, an international effort to rescue children from Nazi-controlled territory was organised by British, Jewish and Quaker leaders. My mother’s fate, among many, hung in the balance. The US Congress considered a bill to accept 20,000 Jewish children but despite over a thousand unsolicited letters offering to adopt a refugee, an isolationist, 'America-first' constituency prevailed. The US Immigration commissioner’s wife warned '20,000 charming children would all too soon grow to 20,000 ugly adults.'

After condemning Kristallnacht, President Roosevelt refused to take a stand on accepting refugee Jewish children—as did many American Jewish leaders--and the bill died.

My mother (and by extension, my sister and I) owe our lives to British resolve and humanitarianism.

The UK government passed emergency legislation and over the next nine months, Great Britain admitted 10,000 Jewish children who arrived unaccompanied from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland on the kindertransport—the children’s transport. It was a massive and impressive logistical operation.

12-year-old Helga, one of the lucky ones, had to endure the rupture of separation from her mother at the Leipzig train station as she boarded with her 11-year old brother Edgar and one small, sealed suitcase. Helga’s father could not say goodbye because he was in prison for smuggling money to his English trading partner to pay for his family’s escape. He had refused to flee earlier, declaring he was a loyal German with World War I medals. How could anyone persecute him? Ironically, prison might have extended his life. The punctilious Germans insisted he serve his full sentence before they released and re-arrested him and sent him to a concentration camp.

As the train pulled away, little Helga waved from the window and watched her elegant mother grow smaller on the platform. It was the last time Helga saw her mutter.

Both my mother’s parents were rounded up and murdered by the Nazis. They along with Helga’s favourite aunt Elsa and over 30 relatives including her grandparents, uncles, and cousins perished at the hands of the German Reich.

The National Socialist German Worker’s Party wiped out my mother’s entire family and obliterated the world she was born into.

All because an insecure, grandiose man from the far right, a populist showman who attacked minorities and elites while fabricating his own aggrieved, conspiracy-peddling super-cult, vowed to restore his country’s greatness.

And because the world stood by and waited too long to combat tyranny, race-hatred and fantasy-mongering aka mass disinformation.

Helga never even received official confirmation of her father’s death. So well into my own teens--30 years later in New York City—a rare late-night message would hint at a sighting of a man who 'could be' my grandfather in a foreign country. It was surreal. My mother’s father who had supposedly died in the Holocaust might still be alive! He was in his mid-thirties on Kristallnacht, so would be in his sixties now.

After frantic phone calls and even transatlantic flights, when ashen embers briefly flared back to life, those hopes were invariably extinguished.

Not until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, was I able to take my mother back to Leipzig and learn the truth. Rooting through a dusty filing system for congregation members at her synagogue, I found my grandparents name on a frayed white index card. The last entry in neat handwriting read 'deported to the east.' I’d heard those words before but never with such bone-chilling finality. They were a well-known euphemism for “sent to a concentration camp.” For my grandfather, this turned out to be Sachsenhausen where I eventually visited the crematoria, the camp gallows and the infirmary where horrific medical experiments were conducted on prisoners.

After being fostered in London, where she slept in an alcove, and educated in a Catholic boarding school, where she turned her feet silently inwards to protest having to say the Lord’s Prayer every morning, my mother met my father in Liverpool. They sailed to Israel and became pioneers on a kibbutz. Picture Ingrid Bergman in shorts with a shovel singing the Jewish national anthem, Hatikva, and vowing Never Again. A national home for the Jewish remnant was a life-or-death imperative and my secular mother remained proud of her small role in helping to build the third Jewish commonwealth in 3000 years in the birthplace of the Jewish people. She would later support ending the 1967 Occupation of Palestinian land conquered during the Six Day War and extending justice to millions of Arabs.

But that was after my parents moved to America, where they made their home for the past 61 years.

My mother loved America and gave thanks for all its boons, grateful for her enduring marriage, her two children and four grandchildren, and her long, tranquil life after such a dark, traumatic childhood.

Helga was not a political scientist but used a moral yardstick for understanding current events. The Russian invasion of Ukraine she lived to see was no exception. Helga believed there were good people and bad people in the world, and she owed her life to good people after bad people had murdered her parents. But one could never rely exclusively on the goodness of other people. You must always be ready to step forward and act. The Holocaust was unique even if individuals may forever seek to appropriate, diminish it or deny it. But for my mother, the abiding lesson was that good people must be prepared to combat evil, in Ukraine as in Germany - or for that matter in the United States, where the rise of a monomaniacal demagogue held disturbing echoes of her childhood.

Good people must always be ready to stand up and fight for themselves or other would-be victims, so that bad people do not blot out the sun and incinerate us.

And so that we might all get the privilege of dying in our own beds at 94, surrounded by our loved ones.

This memoir was first published in 2022 in The American Oxonian, the journal of The Association of American Rhodes Scholars. It was slightly modified for this publication in QUAD but before Israel was attacked by Hamas in October 2023.

Doron Weber is the author of four books, most recently Immortal Bird: A Family Memoir. He works as a Vice President and Program Director at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Picture credits: Doron Weber.