OFF THE SHELF: MARCH 2022

OFF THE SHELF: MARCH 2022

Books that shed light on the Ukraine war, slavery, people trafficking and urban geography

Published: 3 March 2022

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

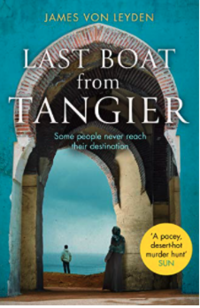

Last Boat from Tangier by James van Leyden (CONSTABLE, 2021)

The author (Oriel, 1974) has written a desert heat murder thriller themed around human trafficking and north Africa. When Detective Karim Belkacem's best friend and colleague, Abdou, goes missing during an investigation into an illegal cartel, Karim is sent to Tangier to look for him. But the Tangier police have another problem on their hands. Thousands of sub-Saharan migrants have collected in the region, desperate to get to the promised land of Europe. Unable to trust his contacts in the police, or anyone in Tangier's underworld of traffickers and informants, Karim turns to his adoptive sister Ayesha for help. The truth behind Abdou's disappearance is more disturbing than either of them could have imagined...

Capitalism and Slavery by Eric Williams (Penguin Classics 2022)

The author (St Catherine’s, 1932), who went on as Prime Minister to lead his native Trinidad and Tobago to independence from Britain in 1962, had enormous difficulty publishing his Oxford doctorate of 1938, finally succeeding only in 1944 in the US.

Racism featured in that difficulty, but it wasn’t as potent an aggravation to his detractors as Eric’s actual arguments, which kicked over the received narrative of how slavery was ended by Britain, and above all why it was ended.

This publication in 2022 by Penguin shows how hopelessly behind the UK has been in discussing and accepting slavery as part of Britain’s troubled imperial past.

The book had already seen three editions by the University of South Carolina, in 1944, 1994 and 2021.

Williams’ doctorate was brilliant and like so many brilliant theses it was wide ranging.

Britain had fallen into a stupendously lazy habit, he argued, of celebrating the emancipation of the slaves as a moral and religious achievement of William Wilberforce (1759-1833) and others around him, known as ‘the saints.’

Williams argued that the true reason for the end of slavery wasn’t moral and religious virtue so much as self-interest expressed as free trade, at a moment in the 19th century when Britain was ascendant in all matters and ruled the waves.

West Indian plantation owners had succeeded under mercantilist conditions that belonged to the 18th century, among them certain navigation laws and preferential duties to protect British trade from competitors.

The big idea of the 19th century was free trade. The result of ending slavery in its own plantations was that the cost of sugar in Britain fell as cheaper supplies became available on the ‘free market’ – which by the 1840s meant slave sugar but from Cuban and Brazilian plantations instead.

None of the sanctimonious saints had much to say about that glaring contradiction, argued Williams, and nor did they have any problem with the cotton that poured into Liverpool and Manchester from slavery sources in the American South.

Viewed purely in economic terms, Britain had climbed the ‘value added’ ladder and could now become rich from manufacturing and exporting, leaving the production of raw commodities to other slaves.

Perhaps the key quote in the whole book, which is offered as economic history rather than as a study of slavery itself, is on page 128:

‘The attack on the West Indians was more than an attack on slavery. It was an attack on monopoly. Their opponents were not only the humanitarians but the capitalists.’

The three key events were the abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807, slavery in 1833 and the ‘sugar preference’ in 1846, says Williams. ‘The three events are inseparable.’

Of course, the subject is staggeringly complex and a ready number of scholars tried to demolish Williams’ argument in the years after its publication, particularly with reference to how well British plantations did during the American Revolution and Napoleonic wars.

To some extent right in details, they missed the broader heft of Williams’ ideas which are weighted towards the 1820s-40s and rooted in Adam Smith’s insights about free markets operating more efficiently than protected ones.

There’s a wonderfully luminous note offered by Williams towards the end of his review of his sources (the hallmark of a doctorate turned into a book, and none the worse for it -) where he cites Marguerite Steen’s best-selling 1941 novel The Sun is My Undoing.

Now this novel, largely forgotten now, was 1,200 pages long and the hero is a slave trader. It sold out on both sides of the Atlantic. The book aroused no criticism of the truth of its essential narrative, which concerned ‘the triangular trade and its importance to British capitalism.’

In a rather discerning way, Williams had pointed out that no one objected to ‘slavery as capitalism’ when it was explored in a swashbuckling historical novel. Only when explored as the essential truth of slavery did it become problematic, because undermining the 'moral virtue' argument of the abolitionists.

The more troubling implication, that lingers to this day, is that some of those who disagreed with Williams were in some sense racist, or in thrall to racist tropes.

Off the Shelf typically concerns books where there is an Oxford connection, whether the place, the University or of course the author.

Alumni can claim 15% discount in any Blackwell's store with a My Oxford Card.

Details about the Oxford Alumni Book Club are at: www.alumni.ox.ac.uk/book-club

Picture Credits: Shutterstock (Listing shot, Ukraine map). Otherwise the respective publishers.