LEARNING FROM THE END OF THE COLD WAR

LEARNING FROM THE END OF THE COLD WAR

Oxford Cold War specialist Archie Brown reflects on the human actors who ended the Cold War

Published: 26 November, 2020

Author: Archie Brown

Share this article

The Cold War began with the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe following the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War Two. It was over by the close of 1989, with the countries of central and eastern Europe independent and non-Communist. Ideologically, the Cold War ended a year earlier. In a remarkable speech at the United Nations in December 1988, Mikhail Gorbachev discarded every major tenet of Marxism-Leninism. Calling for the ‘deideologization’ of international relations, he declared that the people in every country must have freedom to choose for themselves the kind of system they wished to live in.

The following year citizens of the Warsaw Pact countries took Gorbachev at his word. In one country after another Communist rule ended – and the Berlin Wall fell – without a shot being fired by a Soviet soldier. There was serious violence only in Romania where the Ceauşescu regime abhorred and rejected Gorbachev’s ‘New Thinking’. That conflict ended with the execution of the Romanian dictator and his wife on Christmas Day 1989.

The metamorphosis could not have occurred had not a Soviet leader with a very different mindset from any of his predecessors come to power, and had he not used the great authority of his office with political finesse to transform Soviet foreign policy, while simultaneously embracing liberalization and partial democratization at home.

But the great change in the political map of Europe depended also, and crucially, on a policy of engagement pursued by the United States during Ronald Reagan’s second term. Reagan came to prefer the judgement of Secretary of State George Shultz to the scepticism of the Defense Department and the CIA about the possibility of fundamental change in Moscow.

A surprisingly important role – given the disparity between Britain’s defence capacity and that of the two nuclear ‘superpowers’ – was played by Margaret Thatcher. It arose from her exceptionally close relationship with Ronald Reagan who described her as a ‘soulmate’. She was his favourite foreign leader by far and her standing was high in all sections of the divided Reagan administration.

That Thatcher urged Reagan to engage with the Soviet Union and spoke positively about Gorbachev strengthened the president’s own resolve to ignore Washington voices insisting it was a dangerous illusion to believe that any good could be achieved by talking with Soviet leaders.

No British Prime Minister in history met so often with a Soviet leader or with an American president as did Margaret Thatcher. On each meeting with Gorbachev, she became more convinced of the seriousness of his resolve to make the Soviet system fundamentally different from what it had been hitherto. In 1987 he told her that they had not yet been able to move ‘beyond the Stalinist system of administrative government’. This was advance notice of the extent of his democratizing ambitions.

The ‘Iron Lady’, as the Soviet army newspaper had dubbed Leader of the Opposition Thatcher in 1975, had become by 1987-88 a go-between. Her Foreign Policy Adviser, Sir Percy Cradock, who thought her enthusiasm for Gorbachev excessive, later described her as ‘an agent of influence in both directions’. In September 1988, she told Sir Rodric Braithwaite, when he was about to become UK ambassador in Moscow, that if Michael Dukakis defeated George Bush in the forthcoming presidential election, then (among foreign leaders) ‘Gorbachev will be my only friend left’.

Cradock’s misgivings notwithstanding, Western constructive engagement with the new Soviet leadership was a sine qua non of ending the Cold War. Had Reagan and, following a slow start, his successor George H.W. Bush – and Margaret Thatcher, with her rapport with both Reagan and Gorbachev – not helped to build new relations of East-West trust, it is inconceivable that the peoples of Eastern Europe could have sent their Communist rulers packing without Soviet retribution.

Had the Cold War tensions of Reagan’s first term persisted, no Soviet leader could have survived had he acquiesced with ‘the loss of Eastern Europe’. Even in the new atmosphere of East-West co-operation and domestic liberalization, Gorbachev was blamed by conservative Communists and the military-industrial complex for this loss. His response was, ‘To whom did we “lose” them? To their own people’.

Relations between the West and Russia are much worse today than they were when the Cold War ended in 1989 or when, two years later, the republics of the Soviet Union became fifteen separate states, with Russia (which occupied three-quarters of Soviet territory) remaining the largest country in the world, and one which, like the United States, has enough weapons of mass destruction to destroy life on earth.

The Cold War was a struggle on many fronts. Apart from the dangerous military rivalry, there was an ideological struggle in which the Soviet Union headed an international Communist movement with adherents in every country. There was competition also between the radically different political and economic systems on each side of the Cold War divide.

For all the differences between Russia and the West today, they are less deep and comprehensive than those which existed in 1985. Yet that relationship changed dramatically for the better within the space of five years. In the thirty years since then, the deterioration in the relationship is not the responsibility of one side alone. Understanding the process by which the Cold War ended is an important first step in figuring out what has gone wrong since.

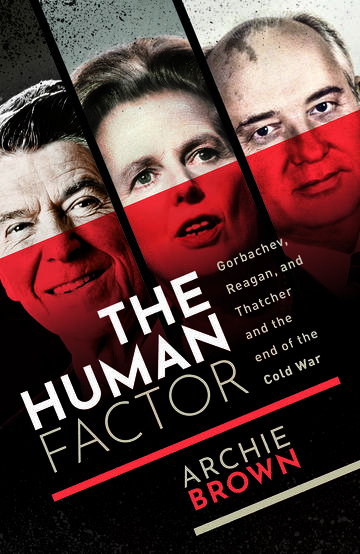

Archie Brown is Emeritus Professor of Politics at Oxford, an Emeritus Fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford, and a Fellow of the British Academy. He is the author of many books on the former Soviet Union and its demise. A Leading authority on Mikhail Gorbachev, he was the first person to draw Margaret Thatcher’s attention to Gorbachev as a reform-minded likely future Soviet leader. His latest book is 'The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War'. Oxford University Press (2020).