HOMINIDS BEFORE HUMANS

HOMINIDS BEFORE HUMANS

Archaeology is red hot right now because it is rapidly solving huge mysteries about the evolution of humans, says Thomas Higham in a remarkable new book

Published: 19 April 2021

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

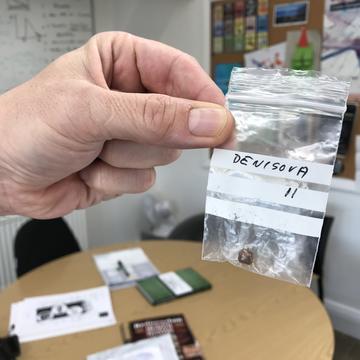

Standing in his office on South Parks Road, Professor Higham shakes a big bag of bone fragments that emit a brittle sound like the clinking of slender shards of broken porcelain.

They are from the ongoing excavation of a remarkable cave system in southern Siberia, specifically the region of Altai, plumb in the centre of Eurasia.

‘In the past,’ says Higham, ‘We would have been left to speculate on the story of these bones. There are too many and they are too alike. But now we have mass spectrometry they can be sampled at a rate of a hundred a day – the chemical signature quickly throws up the result to an experienced analytical chemist: this one a mammoth, that one a hyena, this one a wolf, that one a human.’

The time frames of this archaeological science adventure are mind blowing.

Forget the two-thousand-year span of the traditional Modern History curriculum at Oxford. We’re talking 300,000 years to about 50,000 years ago, the middle and upper paleolithic era.

Go this far back and you’re at a turning point, evolutionarily speaking, where humans are not exactly established yet and where traditionally we are accustomed to talking about Neanderthals as our predecessors, not forgetting the wider hominoidea – upright primates, apes.

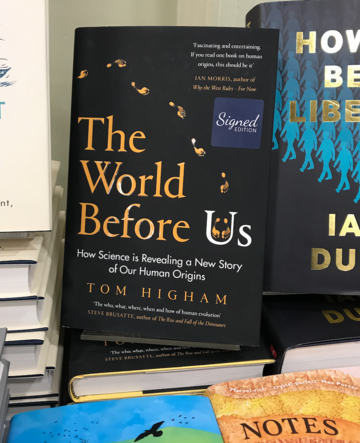

Higham’s book, The World Before Us, How Science is Revealing a New Story of Our Human Origins, is not told as dull science but more as an infectiously enthusiastic detective thriller.

One of the broader precursors is how various sites of archaeological interest have opened up since the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, aided by the thawing out of the tundra by climate change.

The one that the book gathers its central narrative around is the Siberian cave system called Denisova. Professor Higham has visited it many times and waxes lyrically about the sub-alpine climate and landscape, which sounds nothing short of idyllic, not to mention crystal clean air and bubbling brooks of icy water.

Professor Higham’s book starts by confirming the fairly familiar idea that humans originated in Africa, with DNA dispersal to all four corners of the earth following. This narrative was really the product of the 1980s, but the surprising follow up is just how far and fast humans travelled.

The oldest recognisable human, working with the fossil record and a particular site in Morocco, is 300,000 years old, but at this remove the cranial features are still different to ours, leading to the intermediate designation ‘archaic Homo sapiens’. This discovery is also from the late 20th century, the relevant fossil dug up by miners in 1961.

Without wanting to ruin the plot lines of Higham’s adventurous tour of discovery, he manages with the help of a doggedly determined research student to sample through hundreds of bone fragments to alight upon one very unusual and special specimen.

Through mass spectrometry and DNA analysis (cue critical collaboration from the University of York, Max Planck Institute) it is shown to be not only distinctive, genetically speaking, from humans, but to be a hybrid – the offspring of two different and distinctive hominid groups.

This is a real eureka moment and it’s worth the wait.

On a regular visit to the Max Planck Institute in Germany, where the bone fragment was undergoing a special technique of analysis, Higham asked his colleagues ‘What’s the news on Denny?’ Denny is the nickname he’d given the specimen.

The answer came back that a first analysis of the nuclear genome had shown that there were two different types of DNA in this bone sample.

‘It was a hybrid person, the first-generation offspring of two different species of human.’

It’s hard to underestimate the significance of this discovery.

Since the 18th century Enlightenment we have become accustomed to strictly-bordered taxonomies of ever-increasing certainty. One species cannot be another. Higham describes in his book the Lyger – offspring of tiger and lion. Of course, different species can do, and have historically interbred. But the resulting hybrid cannot typically reproduce.

The implication of Professor Higham’s discovery is that distinctly different hominid groups did successfully reproduce.

He’s at pains to point out that in a very basic, perhaps intuitive sense, we’re all an agglomeration of inherited genes from many sources. It was already understood that we have a tiny bit – about 2% - of genetic code from Neandertal sources.

But we’re not just an undifferentiated soup. He talks about genetic diversity and evolution like a braided river system, where distinct channels might coalesce yet remain distinct.

The broader discovery since 2000 is the existence of several genetically distinct hominids. He cites six or seven such distinctive populations, one of them ‘Denisovans’ after the site of the cave, another Hobbits from Indonesia.

In cultural historical terms, this understanding bolsters the Darwinian notion of nature an entangled evolutionary bank of undergrowth rather than a distinct succession.

Were we to re-stage the celebrated evolution debate of 1860, held in what is today Oxford University’s Museum of Natural History, the church side of the debate represented by the ghost of Bishop of Oxford William Wilberforce would lose comprehensively to the ghost of Thomas Huxley, who of course fought the Darwinian position.

Humans are not unique and they aren’t even distinctive in the way we like to assume.

Does this have implications for our self-understanding amidst the pandemic of 2020, shadowed by climate change?

Professor Higham answers, ‘Neanderthals were everywhere but died out. Our amazing technology in 2021 represents a fraction of one per cent of our human history, temporally. Extinction is normal, survival the exception.’

Professor Higham’s book The World Before Us was published on March 25, 2021, by Penguin Random House.

Professor Tom Higham is Professor of Archaeological Science and Deputy Director, Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit; Fellow of Keble College. His research interests focus on archaeological dating, including the radiocarbon dating of bone, as well as the chronology of Palaeolithic Europe. He is involved in a variety of projects investigating the human occupation of Britain and Europe over the last million years and the potential co-existence of Neanderthals with early modern humans.