A SENSE OF DEJA VU

A SENSE OF DEJA VU

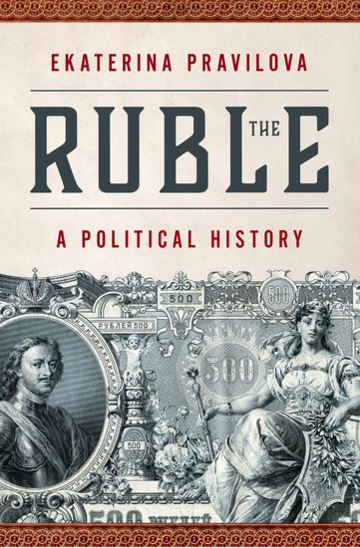

Ekaterina Pravilova has published a timely history of the Russian currency, the rouble

Published: 23 August 2023

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

Professor Pravilova sings the praises of Susan Ferber, her editor at Oxford University Press, who she says is the central reason why she published The Ruble A Political History with Oxford.

Currently Rosengarten Professor of Modern and Contemporary History and Director of the Program in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at Princeton University, and a native of St Petersburg, she confesses that it was never her intention to write a history of the rouble (typically spelt ‘ruble’ in the US) and it has taken seven years to research and write the book.

‘I was actually researching deceit and dishonesty in Russia but then the central problem arose, the grandest deceit of the lot, or fraud if we put it this way, the way that paper money was launched in Russia [in the mid-18th century] physically backed by silver and copper coins.’

‘The ‘fraud’ was that the state pledged to keep paper money exchangeable for the ‘real’ metal money, but was not able to keep this promise,’ she says.

This was during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-96). She writes:

‘But after the government discovered the ease of using paper money to cover extraordinary wartime expenses, it started issuing paper notes that were not ‘backed up’ by the metal collateral.’

When the value of the paper money, then called Assignats, began to fell, the government fell to supporting its value ‘through references to the sublime power of the ruler.’

‘Assignats came to be seen as a projection of absolute authority.’

That, in embryo, is the history of rouble and one of the great themes of Professor Pravilova’s book, the way that a currency becomes a manifestation of politics, but also a shaper of political reality.

We discuss the fact that most currencies go through ups and downs while inflation is the enemy of prosperity; the gold standard was adopted and then dumped at different times in different countries including Britain, with painful consequences for ordinary people.

But the Russian experience is exceptional and the rouble was, ‘except for brief periods,’ inconvertible and indeed existed as a theoretical entity for parts of the Soviet era, while a black market flourished under the radar, a clue as to the deep roots of corruption that blight Russia and many of the former Soviet Republics to this day.

What about Ukraine?

It is a peculiarity of timing that Professor Pravilova has carefully researched over seven years a political history of a currency, whose narrative ends in the years after the 1917 revolution.

Yet many of her book launch conversations have inevitably swung towards current affairs and Russia’s ill-starred invasion of Ukraine.

She sighs and laughs at the same time. Then she says, ‘Well the extraordinary thing is that what is unfolding now has more often than not given me an enormous sense of deja vue. It is not new.’

The week before we speak, in mid-August 2023, the rouble, having devalued to the tune of 25% since the start of 2023, exceeded the symbolic 100 R to one US dollar, prompting the Russian central bank to increase interest rates by 3.5% overnight.

Initially having little impact, at the time of publishing this story the exchange rate had steadied at just over 94 rouble to one US dollar. As recently as June 2022 it had been 54 roubles, although immediately after the invasion it soared to 130.

Over in Siberia someone hijacked a digital bill-board and made it criticise Vladimir Putin for robbing the country.

But exchange rate volatility is nothing new in Russia and not even especially noteworthy, so far at least, if you consider the long context provided by Professor Pravilova’s book.

The state devalued the ruble on the basis of 10:1 in 1947, meaning that if you had $100 in savings it was effectively reduced to $10 overnight.

In 1993, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, roubles began to flood into Russia from all the former Soviet Republics. The government of the Russian Federation decided to rescind all Soviet banknotes issued between 1961 and 1992, for the new Russian money:

‘This exchange, confiscatory in nature and reminiscent of the 1947 reform, once again wiped out people’s savings.’

The then Prime Minister half-jokingly said, ‘We wanted the best but it January turned out as always.’ It is almost a meme these days in Russia, so well-known is this phrase:

‘[Victor] Chernomyrdin’s phrase went viral and came to symbolize the persistence of old patterns in government policy that prioritized state interests over the needs of the impoverished population.’

By some measures – the official figures are not entirely reliable in any state – Russian core inflation remains lower than Britain’s in mid-2023.

But Professor Pravilova, who has family still in Russia and last visited the country in January 2022, insists that where the population is up against the poverty line, a creeping rise in the prize of bread or potatoes is in fact a catastrophe. She is not referring to the wealthy elite in Moscow and St Petersburg but the masses or ordinary Russians trying to survive, in a country where half the population have incomes of €7-8,000 a year.

While Russia adopted a market economy in the 1990s and somewhat contained inflation, it was in truth saved by high hydrocarbon prices into the new millennium, with oil and gas sales pouring hard currency into the system.

The Russian rouble was never fully convertible even during this period, Pravilova explains, but it absorbed the cost of a decade of war in Chechnya, the 2008 invasion of Georgia, and the annexation of Crimea and occupation of Eastern Ukraine from 2014 onwards.

In terms of the history of the rouble, the significance of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 is that western sanctions denied the rouble its convertibility, she argues:

‘The unexchangeable rouble turned again into the symbol of Russian authoritarianism and autarky.’

Regarding Russia as a state, Professor Pravilova says that her generation has a pang of guilt over the way that Putin went far beyond ending the free-for-all of the 1990s, arguing apparently successfully that people preferred economic prosperity to freedom, ‘a sneaky way of making people complicit with Putin.’

‘That is in fact wrong. It is of course possible to have a less intrusive state and still have prosperity. But it is not what Russia is today.’

Based on Russia’s experience under Putin, she adds what could be read as an ominous warning to the supporters of populist strongmen leaders wherever they be:

‘Any monetary calamity is always at the expense of the people. The state always wins.’

The Ruble A Political History was published by Oxford University Press on 27 June 2023.

Ekaterina Pravilova is Rosengarten Professor of Modern and Contemporary History and Director of the Program in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at Princeton University. She is the author of the award-winning A Public Empire: Property and the Quest for the Common Good in Imperial Russia, as well as Legality and Individual Rights: Administrative Justice in Russia and Finances of Empire: Money and Power in Russian Policy in the Imperial Borderlands, published in Russian. She is a native of St. Petersburg.