THE MAN FROM ALL SOULS

THE MAN FROM ALL SOULS

Oxford moral philosopher Derek Parfit is now the subject of a major biography

Published: 30 March 2023

Author: Richard Lofthouse

Share this article

The author should be congratulated. This is both a fabulous book and a necessary biography of a significant Oxford academic who a lot of people have sort of heard of but can’t quite place: Derek Parfit (1942-2017) (Balliol, 1961), or as Edmonds offers, ‘the most famous philosopher most people have never heard of.’

One reason for that relative obscurity is Parfit’s reclusive nature and relative lack of ego, but that shouldn’t be confused with his enormous stature among many but not all other philosophers, as a man who devoted his entire life to rebuilding moral philosophy in the absence of God.

Even those few statements open various cans of worms. He was searingly bright as a young man and won every prize going, first at the Dragon School in Oxford, where his parents moved after a life as Christian missionaries in China, and then at Eton. The latter in particular gave Parfit ample confidence in his intellectual abilities and as Edmonds makes plain, he viewed rules as inconveniences for other people – he constantly wrote to various committees of various scholarships, asking if he might rearrange everything to a different timetable, to suit Derek Parfit. So it is not true that he didn’t have an ego. He even invented quotations on some known occasions, which remains awkward but also evidence of his intellectual self-confidence.

And then there is the difficult family narrative and the ex-missionary parents. Derek was born in China, in Chengdu, in 1942, amidst Japanese air raids. His parents lost their faith while there and subsequently suffered from a difficult marriage, as much as the evidence presents. His father Norman ‘went native’, becoming a Maoist and according to Edmonds ‘ingeniously interpreting this to be consistent with his pacifism.’ When they left, Derek had to sit under a gun turret in a Liberator bomber. His relationship to his father was difficult, a recurrent theme in the book.

I think that family psychologists would have much to say about the young Derek, who was sent to board (weekly, admittedly) at the Dragon despite the family home being a short walk away at 5 Northmoor Road, and money evidently short.

In this enormous sense it’s not too far a push to see the young child/man/scholar harnessing together an acute awareness of loss of faith with emotional turmoil, first hand fear of mortality as an infant and the sort of nihilism he would have read about more widely in works by the likes of Friedrich Nietzsche.

The fact that he then devoted his entire life to ‘saving moral philosophy’ without God, is a consistent result but might now seem to have been fanciful, or at least a cul-de-sac. Even religion requires a leap of faith, so it would seem bizarre to think that one man could hold the whole edifice up having first built it, on the basis of a rationality hotly disputed amongst a small number of professional western philosophers, from a room in All Souls.

There are wonderful tales of eccentricity, such as making instant coffee from the hot tap to get the caffeine as quickly as possible so as to devote even more time to philosophy and only philosophy. His wind-down routine involved very long baths and washing down anti-depressants with tall glasses of vodka, barely emerging the next day before noon and certainly failing to talk to guests at college dinners in the way that might have been minimally expected.

There was a dark side to this. He drove his editorial team at Oxford University Press to despair, and actually to the point of complaint; while his partner and eventual wife Janet Radcliffe Richards, a philosopher in her own name, noted later than she remembered no occasion when they didn’t do what Derek wanted. In other words he was almost wholly selfish, and yet much loved and invariably kind.

He was also insanely generous in the purely professional sense, responding to questions and manuscripts from colleagues and students with massive, closely written responses turned around in frighteningly shortframes.

Parfit’s defining work Reasons and Persons (finally published after the severest imaginable intellectual and practical anguish to all parties on April 12, 1984, by Oxford University Press) is compared by Edmonds to arriving at a restaurant and being offered ‘pizza, sushi, burgers, curry, plus a hundred little tapas dishes.’ In other words it was incoherent, or at least indigestible. But it also opened up all sorts of possibilities for moral philosophy in ways that his other major contribution, On What Matters (2010), appears not to, based here on Edmonds’ commentary.

In particular, Parfit is held to have opened up a whole sub-genre about unborn populations of humans and our responsibilities towards them, a powerful tool in the face of climate change and other existential risk. He also supported the Effective Altruism movement which claimed to stem partly from his thought and was brought to life by younger Oxford figures such as William MacAskill and Toby Ord (he also criticised elements of it).

Dr MacAskill is an Associate Professor in Philosophy and Research Fellow at the Global Priorities Institute at Oxford and co-founded in 2009 with Dr Ord Giving What We Can, which encourages people to give 10% of their income to effective charities.

Meanwhile Janet is Professor of Practical Philosophy and Distinguished Research Fellow, Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics. Parfit had nothing to do with its founding in 2003, Edmonds makes clear, ‘but it was the natural institutional culmination of his pioneering seminar, three decades earlier, with Jonathan Glover and Jim Griffin.’

What no one disputes is Derek’s perfectionism, which could be obsessive, or his devotion to rebuilding, or saving, morality without God, but the project itself was always an expression of a broader human crisis that any modernist would recognise at a hundred paces.

One thinks back to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and Mr Ramsey, typically held to have been a stand-in for her polymath father Sir Leslie Stephen (1832-1904) who could romp through all the letters of the philosophy alphabet to ‘Q’ but what about R and S and T and up to Z?

Even titans fall short, as man plays at God and doesn't quite pull it off. Cue the crisis we call modernism and/or modernity! Well that feels like Parfit. A historian before he turned to philosophy, Derek’s anxiety about the objectivity of moral truth is to some extent ours.

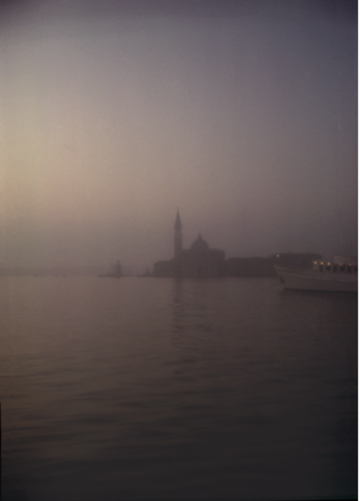

Another side of Parfit was his photography. Far from being a sidelight to the philosopher, it is given plenty of narration here and proves very insightful. He decided that Venice and St Petersburg were the only cities worth the candle and visited both every year with his camera and on occasion with colleagues, not always agreeably. They were certainly not romantic trips. Instead he got frostbite standing around in St Petersburg waiting for the light to ‘be right’, so much so that a local suddenly started to rub snow in his face having seen the symptoms, so that he thought he was being attacked. It was all extraordinary and makes for great copy. The KGB were probably bugging him but all they would have got was photo buffery plus abstract philosophical commentary.

Edmonds reflects that Parfit got insolubly tangled up in population ethics, and whether a huge population of humans living mediocre lives would still offer a higher quantum of happiness than a smaller number of humans living very happy lives. Such utilitarianism is now being rapidly superseded by planetary limits intensified by climate change. We may no longer be in control of our future. Parfit could have widened his lens to such outcomes but there is no evidence that he did.

There’s also an illuminating section of the biography where the author notes that Parfit’s otherwise original early thought on personal identity isn’t unlike weak-brew Buddhism, which de-centres Western individualism for something more fluid.

Did it require this much personal anguish to reinvent a wheel that had been happily turning in Asia for millennia? And once again, some of this earlier thought merely echoes early twentieth century modernist inquiry which fed voraciously on European and English language translations of non-western religion and mysticism, from Buddhism to Zoroastrianism.

Rightly left until the end, autism is raised by Edmonds as a condition that Parfit probably suffered from, but he also had an insight into it himself. It was a mighty paradox to be so maniacally devoted to moral philosophy and yet so apparently indifferent to flesh and blood humans around him, and yet so kind to all – the word is the one used repeatedly by people who knew him.

And so there falls a section where a comparison is drawn to Wittgenstein, both of whom had an otherworldly air, both of whom were a bit saintly. One ex-student says that being taught by Parfit was ‘very much like a religious experience.’

His colleague at All Souls Richard Jenkyns, said, ‘He was, I think, both entirely selfish and entirely benevolent – an unusual combination.’

Yet here is an edge. Parfit argued once that if you leave a broken bottle on the ground and a child, not yet born, cuts their foot on it one hundred years from today, you shoulder exactly the same burden of guilt as if it happened today. It will be a curiously dull reader to complete this volume and not be affected by some of the powerful ideas that are raised along the way.

Parfit: A Philosopher and his Mission to Save Morality by David Edmonds (Princeton University Press, April 18, 2023).

David Edmonds is a writer and philosopher whose many critically acclaimed books have been translated into more than two dozen languages. He is the co-author, with John Eidinow, of the bestseller Wittgenstein's Poker, and with Nigel Warburton cohosts the podcast Philosophy Bites.

Portrait of Parfit shows him lecturing in Oxford in 2014 Credit: Toby Ord. All other images were taken by Derek Parfit, credit Janet Radcliffe Richards. In order from top, the view from Derek's room in All Souls College, Oxford; San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, also the image that served as the cover of Reasons and Persons; St Petersburg, from the Neva Embankment; and All Souls twin towers, North Quad.