ALUMNI STORIES: 'I REMEMBER REALLY WANTING TO FIND OUT WHAT IT MEANT'

ALUMNI STORIES: 'I REMEMBER REALLY WANTING TO FIND OUT WHAT IT MEANT'

Dr Franziska Kohlt (Brasenose, 2013) discusses how 19th c. science influenced children's literature like Lewis Carroll, and how she didn't think Oxford was 'a place for someone like me'

Published: 3 February 2021

Share this article

What was your favourite book as a child?

That’s hard! I had so many favourites.

But one that really stuck with me all my life is The Flying Tree, by the Syrian-German writer Rafik Schami. It’s a fairy-tale about a little tree that sprouts between a dashing young apricot, and a grumpy old apple tree. The mature arboreals tell the sapling it must choose, wisely, if it wants to become a modern, fashionable apricot, or a reliable, solid apple. But, instead, the little tree falls in love with the sun, the moon the stars – and especially the swallows, who sit in its branches and tell stories about their journeys making the little tree sprout leaves in the image of the birds and their tales. When autumn comes, the tree does not, like others, throw off the fairy-tale leaves that made it who it is, but flies, with the swallows carrying it, to a place where they happily ever after exchange stories for shelter in that tree’s unique crown.

I found that was a very beautiful way of telling kids they can just own their thing, even if it doesn’t quite fit the pre-fabricated boxes life puts before them to tick, and I’ve read it to many kids since.

What initially drew you to study at Oxford?

I think it would be dishonest to say I was drawn to study at Oxford, quite the opposite, in fact, I didn’t think it was a place for someone like me, someone who wasn’t ‘classic Oxbridge material’. I’d grown up on a council estate as a child of immigrants – kids like me don’t go to Oxford, right?

What drew me to it, can perhaps be described as archaeological. I had a project: I had struck upon this thing, that around the same time in the 19th century quite a lot of others, with a very similar background, both in the sciences, and in the church, started writing very similar fantastical stories. They shaped a language, and worlds in which they thought about the baffling new discoveries of science, and explore their implications, by mentally travelling through the worlds implied between the lines of scientific text books, like mythological heroes, just more real, and more critical – and yet, somehow everyone kept telling me fantasy was childish, and not at all serious.

What I needed for my project was basically a time machine, that would let me get to these textbooks, enter the mental space that were shaped by them, and create these stories. I found that in the Bodleian collections, the archives of the museums for the History of Science and Natural History, and in Oxford itself, which, despite being in so many ways at the forefront of research, was in other ways, seemingly frozen in time.

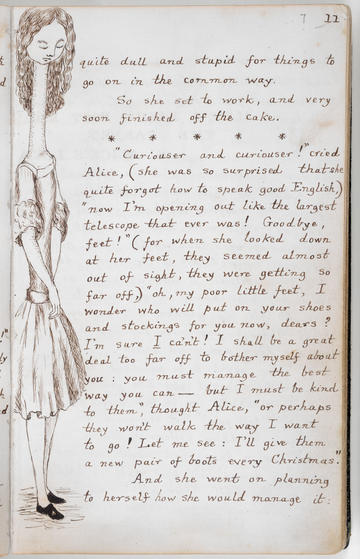

Your DPhil encompassed one of Oxford's most famous authors, Lewis Carroll. How did your fascination with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland begin?

I saw the 1951 Disney cartoon in the cinema, and I was spellbound, but didn’t really understand what was going on at all! That bugged me, and I remember really wanting to find out what it meant. I annoyed my mum so much that she took me to the library, where we found this book, The Other Alice – an illustrated history of Alice. It explained how Lewis Carroll wrote the story for a little girl (my age!), and how hid little hints to the place and time in which they lived in the story, such as the Dodo bird, details from Christ Church’s dining hall, or parodied Victorian educational poems.

That there were stories below the stories – not only in literature, but in every word of every language, how we almost inevitably wrap our thoughts in stories before we send them into a journey through the world – changed my outlook on literature for the rest of my life.

What do you think made books by Carroll, Kingsley and Wells so successful and enduring?

I am asked that question a lot about Alice in Wonderland, and if you look at the political caricatures sections of newspapers over the past 150 years, you can see why. Alice is brilliant satire, and, as I often say, we’ve all sat in a meeting that’s seemed to us a little bit like the Mad Tea-Party! It’s so successful because we can relate.

Alice does a really enticing thing: she goes below the surface of the waking world, literally, but also figurately, and her journey exposes what really lies beyond there. She holds up a magic mirror that exposes what the real face of reality is, and to us, who are part of it, even if we don’t like what we see.

Carroll was quite explicit about the aim of his story, he wanted it to be cathartic, and that was the case for many authors, including Kingsley and Wells and many that took inspiration from her writing.

The way in which they extrapolate an imagined world from the facts of the worlds that surrounds us every day is an incredibly appealing thing to do, and resonates with us, because it’s something we do every day, but are often, for all sorts of reasons, encouraged not to.

Yet that changes little about the fact that it is, when we see that caricature of the politician as an Alice in Wonderland character that tickles a cathartic laugh out of us.

You've said before that the division between disciplines (ie science, humanities) wasn't as stark in the 19th century as it is now, how do you think this influenced academia and literature?

That’s true – that strikes me every time I tell people I study science and humanities, and the response is: “Oh, weird!”, but when I tell them “Did you know Charles Dickens, or, Lewis Carroll were really into science (while mostly famous for doing literature)” they say “Oh, cool!”

One of my favourite examples for illustrating this, is science literature for children from Carroll’s time, where science and humanities really work together in ways that are actually not so incomprehensible to us today. Many children’s science books were conceived along the lines of going on a magical journey, like through the microscope, into those invisible worlds that explain how things work in the world. These stories were fantastical and educational at the same time.

In many ways, and that was true then and now, children’s literature is the ideal medium to discuss difficult and puzzling topics, because we accept that children still have to learn how things work – somehow, it seems much trickier to accept that this is also the case with adults.

But such quirky Victorian children's tales can actually teach us a lot there. Numerous studies have shown that such narrative techniques – discover, wonder, paired with learning something practical – are just as effective for adults. Think for instance of the enchanting journeys on which David Attenborough has taken you, and how they’ve had the power to profoundly change how we see the world.

Do you think that this is something that should be brought back into academia now?

Absolutely! And, in fact, these fields actually already exist, and it’s incredibly important that they are expanded and funded.

The challenges we face today show that the dialogue between disciplines is absolutely vital.

Take climate change, it is of course, incredibly important to understand how the science of it works, but it is just as important to find ways of conveying this to the public, to politicians and to stakeholders in industry, in such a way as to make them grasp what implications this has for them, our world, and our communities, and what actions need to be taken. And perhaps even more importantly, how to tell them that in such a way that they want take these actions, and feel they are meaningful.

In the past year I have been monitoring the narratives employed to communicate about COVID-19, and recorded what narratives have moved people and politicians, and whether that made them follow the behaviours that scientific findings have recommended, or perhaps steered them away from that, even when the opposite was intended.

The way in which we come to understanding the world, and make decisions within it is so hugely influenced by narratives, which, however, can not only convey facts about, but also distort realities, and direct actions in sometimes damaging directions.

That’s why we need to acknowledge that storytelling is immensely important in, and to science – and teach and understand its mechanisms. This is one of the ways in which interdisciplinarity is really vital to society.

What did you find was the greatest challenge of your DPhil?

Funnily enough, precisely the thing I set out to do: justifying that the bits between the lines, between the disciplines were the thing that needed to be examined. A bit like the little tree arguing with the apple and the apricot tree. And, without meaning to sound rude, I met quite a few of those apricot and apple trees – but thankfully also lots of swallows.

How has Oxford changed you?

The most positive thing I learned was to be confident and assertive of where my research, and my work within the community of Oxford, was leading me, and if those paths didn’t yet exist, to establish these opportunities.

And I was lucky enough to be able to share these experiences from my own academic and personal journey with many fantastic students I taught, and worked with in my capacity in student welfare, many of whom have gone on to amazing and wonderful journeys. And I’m looking forward to hearing the stories of their amazing journeys they will tell in the future.

In July she was featured in BBC4 In Our Time episode Automata, listen to it now.

You can find out more about Franziska's work on her website: https://franziskakohlt.com/

Here is a film Franziska made with Graduate Admissions further exploring the influence of science in Victorian literature:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/mq9jQBMtu3s?list=PLZNrJ2hUOimxPUAFhwiQVfex3YQnzl-qv